In this section

- Does exposure to hazardous work decrease for child labourers identified by a CLMRS?

- Does school participation improve for child labourers identified by a CLMRS?

- Which contextual factors are related to whether children stop doing hazardous work once identified by a CLMRS?

- How do different types of remediation support perform in comparison, in terms of stopping children from doing hazardous work?

- How do different types of school-related remediation perform in comparison, in terms of increasing school participation?

- References

How likely are child labourers identified by a CLMRS to stop working?

- Data from follow-up visits to children previously identified in hazardous child labour under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Summary statistics.

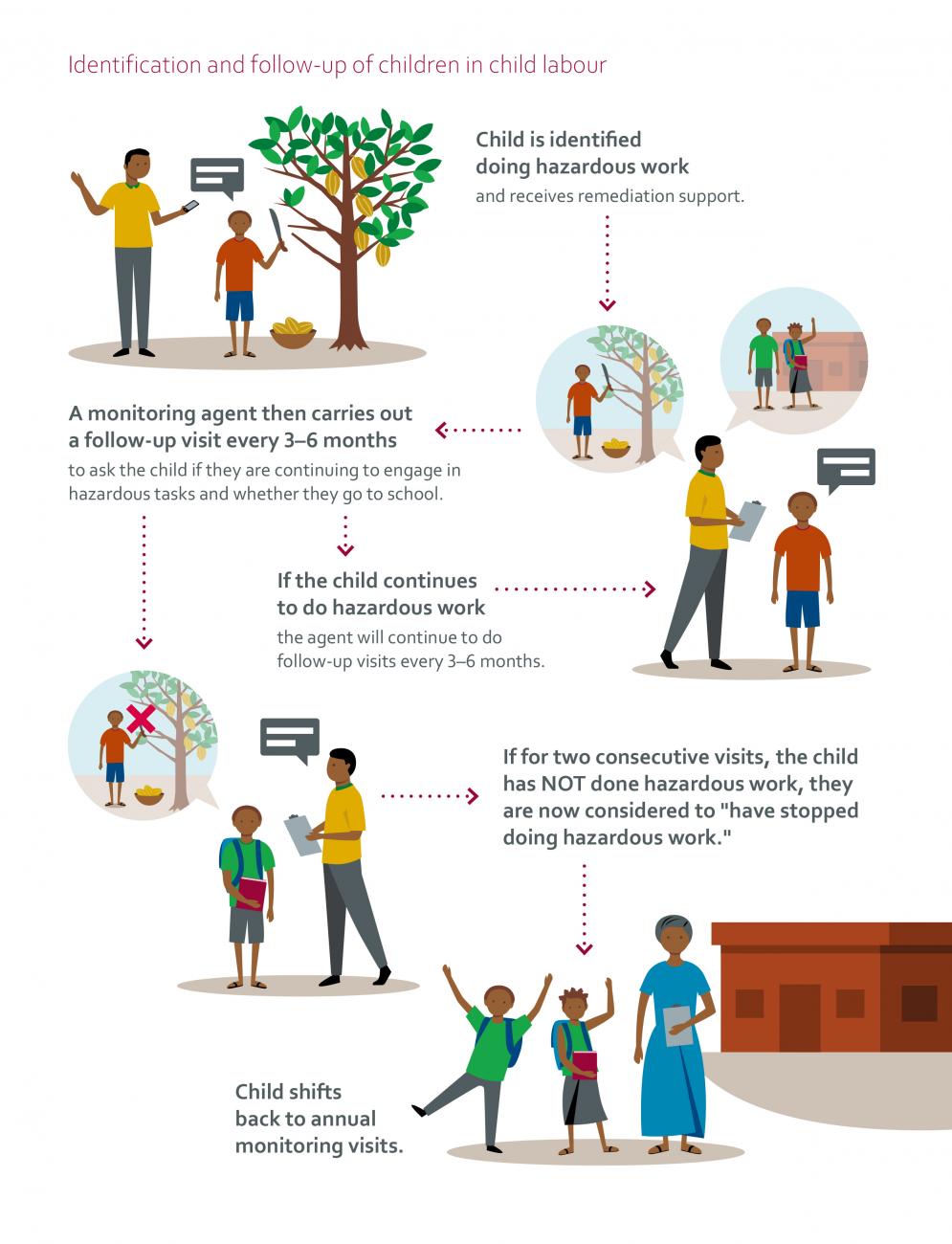

Follow-up visit: under the ICI CLMRS model, after a child has been identified in child labour and received a remediation, the monitoring agents make follow-up visits to the child in intervals of 3–6 months to check whether the child has stopped to do hazardous work.

Child has stopped doing hazardous work: a child previously identified in child labour has claimed to no longer be doing hazardous work during two consecutive follow-up visits.

Sequences of follow-up visits available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire. The validity of results for other contexts may be limited.

Few children in the data base with a history of child labour, who received remediation and stopped hazardous work as confirmed by two follow-up visits, were then visited again after the second follow-up visits. It is therefore difficult to derive from this data a benchmark

criterion to declare a child has definitely stopped hazardous work.

The method we use

We examine the evolution of identified cases of child labour over a sequence of follow-up visits under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.39 Children identified in hazardous child labour under the ICI CLMRS typically receive one or more types of remediation support (assistance, goods or services) tailored to their needs shortly after their case has been identified,40 and are then visited again by the monitoring agent in intervals of typically 3 to 6 months. During these follow-up visits, the agent asks the child whether they continue to engage in hazardous work and whether they go to school. These follow-up visits continue until the child has claimed to no longer be engaging in hazardous work during two consecutive visits. The child is then considered to “have stopped doing hazardous work” under the ICI CLMRS model, and would shift back from the closer follow-up visits to the normal cycle of annual monitoring visits. If the child continues to do hazardous work, the agent will continue to do follow-up visits every 3–6 months.

For all ICI-implemented CLMRS projects in Côte d’Ivoire, the data base contains complete follow-up visit records from a total of 16,869 children aged 5–17 who had previously been identified in child labour (including records up to January 2020). Of these, 6,654 children have only had one follow-up visit; the remaining 10,215 children had at least two follow-up visits. This is the sample of children on which we can examine the effectiveness of the CLMRS in stopping child labourers from doing hazardous work.

What we find

Of the 16,869 children previously identified in hazardous child labour and followed up under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, 38% reported no longer doing hazardous tasks during their first follow-up visit. As explained above, most of these children had more than one follow-up visit. When we take all follow-up visits into consideration, we find that 54% of children previously in child labour reported no longer doing hazardous tasks during one of the follow-up visits (table 4).

We can also see in the data that it is not uncommon for children to switch back and forth between doing and not doing hazardous work from one visit to the next. Among all child labourers who during one follow-up visit reported no longer doing hazardous tasks, 24% again reported doing hazardous tasks during a subsequent visit. Hence, when a child previously in child labour declares not doing hazardous tasks at one follow-up visit, while this is a temporary improvement of the situation, it is not sufficient to consider the case of child labour to be resolved.

When we apply a criterion of not having reported any hazardous work for at least two consecutive follow-up visits, we find that 29% of the children previously in child labour have stopped engaging in hazardous work under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

Table 4: Rates of children previously identified in hazardous child labour under ICI CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire who have stopped working over the course of follow-up visits.

| # of children | Rate within relevant subset of child labourers |

|---|---|---|

Children previously in hazardous child labour and followed up with at least 1 visit | 16,869 | |

Children previously in hazardous child labour and followed up with at least 2 visits | 10,215 | |

Children previously in hazardous child labour who were not doing hazardous work during the first follow-up visit | 6,365 (of 16,896 children | 38% |

Children previously in hazardous child labour who were not doing hazardous work during the most recent follow-up visit | 8,193 (of 16,896 children | 49% |

Children previously in hazardous child labour who were not doing hazardous work during 2 consecutive follow-up visits (i.e. children who stopped doing hazardous work) | 2,981 (out of 10,215 children | 29% |

Children previously in hazardous child labour who were not doing hazardous work during one (or more) follow-up visit(s) | 9,044 (of 16,896 children | 54% |

Under the ICI-implemented CLMRS, a child who has reported not doing hazardous tasks during two consecutive follow-up visits is shifted back to a regular monitoring cycle with less frequent visits. In the ICI CLMRS data base for Côte d’Ivoire, there are 880 children who have a history of child labour, have stopped doing hazardous work after a sequence of follow-up visits, were still below the age of 18 and were visited again at least once under the regular monitoring cycle. Of these 880 children, 20.5% were found to have fallen back into hazardous child labour again. However, if we apply an additional criterion that at least 3 months must have elapsed between the last visits, the share is reduced to 16.3%.

It is not uncommon for children to switch back and forth between doing and not doing hazardous work from one visit to the next. Because of this, one follow-up visit is not sufficient to consider the case of child labour to be resolved.

What we conclude and recommend

The sequences of visits to individual children provide a valuable data source to help understand the dynamics of child labour in the context of CLMRS in cocoa production. First of all, the data shows that children who appear to be out of child labour during one visit may again be found in child labour when visited a few months thereafter. Our first key conclusion from the data is that more than one follow-up visit is needed to verify that a child has stopped hazardous work after having received remediation support. The data does not yield a clear recommended benchmark on the number of follow-up visits and the minimum time period of close follow-up. Under the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, when children report no longer doing hazardous work during two consecutive follow-up visits, the risk of falling back into hazardous child labour thereafter is only 21% (note that this estimate is based on a sample of only 880 children).

More than one follow-up visit is needed to verify that a child has stopped hazardous work.

- More than one follow-up visit is needed to verify that a child has stopped hazardous work after having received remediation support.

- Sequences of visits to individual children provide valuable insights into the dynamics of child labour in the context of CLMRS in cocoa production.

- Under the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, among previous child labourers who no longer report doing hazardous work during two consecutive follow-up visits, the risk of falling back into hazardous child labour thereafter is around 21%.

Does exposure to hazardous work decrease for child labourers identified by a CLMRS?

- Data from follow-up visits to children previously identified in hazardous child labour under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Summary statistics.

- Number of different hazards to which a child is exposed.

- Number of hours a child works on working days.

- Number of days a child works per week.

Sequences of follow-up visits available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire. The validity of results for other contexts may be limited.

Further work is needed to develop tools to measure the severity and intensity of child labour currently available and used under CLMRS.

The method we use

We take a closer look at child labourers identified under the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire who continue doing hazardous work after they have received remediation, to check if their child labour situation is found to be alleviated, even if not fully resolved. Our data allows us to check progress on a limited set of indicators of child labour severity or intensity: the number of different hazards to which children are exposed, the number of hours a child reports to work on working days and the number of days a child reports to work per week.41 For each of these indicators, we check for each follow-up visit whether the situation of the child has improved (i.e. the child is exposed to less hazards or works less hours or days), remained the same or deteriorated (i.e. the child is exposed to more hazards or works more hours or days), compared to the previous visit. To check for progress in terms of hours worked per day, and days worked per week, we include only children aged 10 years or older at the time of the interview. This is because it is very difficult for younger children to provide reliable estimates of the time they have spent doing a certain activity during a given reference period.

What we find

Child labourers identified under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire report being exposed to 1–13 different hazardous tasks when working on the cocoa field, with an average of around 2 different hazardous tasks. If a child labourer followed up under the CLMRS continues to do hazardous work, their exposure to different hazardous tasks decreases slightly on average from one visit to the next.42 Across all follow-up visits where children reported that they continued to do hazardous work (4,750 visits), 23% of the interviews recorded exposure to fewer hazards as compared to the previous visit and 19% of the interviews reported exposure to more hazards (for the remaining 59% of visits, the number of hazardous tasks reported was the same) (figure 9).

Figure 9: Across all follow-up visits where children reported that they continued to do hazardous work (4,750 visits).

Next, we look at the number of hours children reported working on a working day, which is on average 3.2 hours for those children who continue to do hazardous tasks and who are at least 10 years old. From a total of 3,920 visits, during 27% of visits children reported working fewer hours per day as compared to the previous visit, as against 30% of visits where children reported working more hours (for the remaining 42.4% of visits children worked the same number of hours) (figure 10).

Figure 10: Number of hours children who continue to do hazardous tasks and who are at least 10 years old reported working each workday.

To check progress on the number of days worked per week by children who continue to do hazardous tasks, we again include only children who are at least 10 years of age. On average, working children in the sample of children above the age of 10 followed up under the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire report to work on three days per week. From a total of 3,907 visits for which this information is available, during 27% of visits children report working on fewer days per week, as against 29% of visits where children report working on more days per week, compared to the previous visit (for the remaining 45% of visits children reported working the same number of days) (figure 11).

Figure 11: Number of days children who continue to do hazardous tasks and who are at least 10 years old reported working per week.

What we conclude and recommend

We find that under the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, children who continue to do hazardous work are exposed to fewer different types of hazard when followed up, but that on average, there no reduction in how often and for how long they work. However, this average masks differences from one case to another: almost one in three children report a reduction in the number of hours or days worked, whereas for another one in three children, the number of hours or days worked has increased over time.

CLMRS can help not only to identify whether a child is in child labour or not, but also to monitor the extent to which they are exposed to hazards. Tools to measure, and concepts to classify levels of child labour severity and intensity still need to mature, but CLMRS implementers should make efforts to further develop and improve the respective modules in the data collection tools, for example by asking for information on the number of tasks, hours and days worked. Given that many children move frequently from “in child labour” to “not in child labour” and then back into child labour again, it is important that a CLMRS allows us to understand individual cases in more detail and to differentiate between more severe and less severe cases.

- Children who continue to do hazardous work experience a slight reduction in the number of hazardous tasks they do, but on average, we see no reduction in how often nor for how long they work.

- Some children’s child labour situation improves over time while for others it is becomes more severe.

- CLMRS should monitor not only whether or not a child is in hazardous child labour, but distinguish between more severe and less severe cases.

- CLMRS should be able to identify cases where the severity and intensity of child labour increases over time and to prioritise these children for support.

Does school participation improve for child labourers identified by a CLMRS?

- Data from follow-up visits to children previously identified in hazardous child labour and out of school under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Summary statistics.

Child is out of school: child currently not enrolled in school, includes children who were never enrolled in school and those who dropped out.

Child brought into schooling: child has been enrolled in school during two consecutive follow-up visits.

- Sequences of follow-up visits available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire. The validity of results for other contexts may be limited.

The method we use

We assess how children’s school participation evolves while children are being monitored and receiving remediation support under the CLMRS. We use data from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, which provide sequences of follow-up visits for a substantial number of children. Under these CLMRS, a total of 4,472 children identified in hazardous child labour were out of school at the same time. Amongst these, we pay special attention to children of primary school age (12 years or younger), and we distinguish between those living in communities with a primary school present (1,217 children) and those living in communities with no primary school present (673 children). For each of these children, we check whether by the time of a follow-up visit they have started going to school. Similar to the criterion of whether a child has stopped hazardous work, we also apply the criterion of whether a child is enrolled in school during two consecutive follow-up visits. We have data from 882 primary-school age children previously in hazardous child labour and out of school who then had at least two follow-up visits.

What we find

For context, school enrolment is at the same level amongst child labourers as amongst non-child labourers: amongst all children identified in hazardous child labour under the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, around 73% are enrolled in school, as against 72% amongst children not in hazardous child labour.

Amongst all children identified in hazardous child labour and out of school under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, 18% had started going to school by the first follow-up visit. Within the same sample but including only children of primary school age (12 years or younger) living in communities with a primary school present, 26% had started going to school by the first follow-up visit, while 31% were in school during the most recent follow-up visit. Amongst those who had at least two follow-up visits or more, 20% were going to school during two consecutive visits.

In communities where no primary school is present, the corresponding rates are lower, but still remarkably high: amongst primary school age children previously identified in hazardous child labour and out of school at the same time, but living in a community with no primary school present, 19.5% had started going to school by the first follow-up visit and 24% by the most recent visit. Amongst those who had at least two follow-up visits, 14% were going to school during two consecutive visits.

18% of out-of-school identified in child labour had (re)started attending school by their first follow-up visit.

What we conclude and recommend

For child labourers who are out of school, CLMRS generally aim not only to address their engagement in hazardous work, but also to improve their access to education. For the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, we find considerable achievements in terms of improving school participation amongst child labourers, with around one in four out-of-school child labourers starting to go to school under the system. Nevertheless, CLMRS effectiveness in terms of bringing children to school falls short of its success in terms of stopping children from doing hazardous work.

Exposure to work-related hazards and at the same time being deprived of schooling makes a child particularly vulnerable and in need of support. The following recommendations emerge:

- CLMRS data collection tools should include questions to determine a child’s schooling status.

- Children in child labour and out of school should be prioritised for support.

- The ability of CLMRS to help out-of-school children back into school should receive more emphasis in communication and reporting. Improvement of children’s access to education should also be included as a key performance indicator of a CLMRS.

- CLMRS aim to improve children’s access to several fundamental rights (education, identity, etc.), as well as to address child labour.

- Children who are in child labour and out of school at the same time are particularly vulnerable and should be prioritised for support under CLMRS.

Achievements in terms of school enrolment should be given more attention in CLMRS communication and reporting, and they should feature among key CLMRS performance indicators.

Which contextual factors are related to whether children stop doing hazardous work once identified by a CLMRS?

- Data from follow-up visits to children previously identified in hazardous child labour under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Child has stopped doing hazardous work: a child previously identified in child labour has claimed to no longer be doing hazardous work during two consecutive follow-up visits.

- Sequences of follow-up visits available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire. The validity of results for other contexts may be limited.

The method we use

We examine which characteristics of the child, the household or the community affect how likely it is that children stop doing hazardous work under CLMRS. We use sequences of follow-up visits under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.43 For a child previously identified in hazardous child labour, we define “having stopped hazardous work” as not having done hazardous tasks for at least two consecutive follow-up visits. Since several factors are at play in parallel and may act in combination, we use a logit regression model specified as follows:

- Units of observation are children previously identified in hazardous child labour.

- The dependent variable is whether a child has stopped doing hazardous work.

- As explanatory variables we include:

the child’s age and sex

whether the child was enrolled in school at the time they were identified in hazardous child labour

whether the child is living with at least one biological parent

whether the child has older siblings

the number of household members (indicator variables for whether the household has up to 5, 6–10, or more than 10 members)

whether the head of household and the spouse of the head of household can read and write

whether the household is headed by a woman

whether there is a primary school in the community

whether the community is accessible by road all year round

whether the community is connected to the electricity grid

We sequentially add these child, household and community characteristics to the regressions in order to spot potential instances of multicollinearity.

Around 30% of child labourers identified by the system stop doing hazardous work.

What we find

Overall, 29.2% of children stop hazardous work (defined as not doing hazardous work during two consecutive follow-up visits), when we look at the sample of children identified in hazardous child labour under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire and followed up with at least two consecutive visits.

The regression results show several factors which have a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of a child stopping hazardous work:

- Girls are more likely than boys, by around 2 percentage points, to stop hazardous work.

- Children who were in school at the time they were identified in child labour are more likely, by around 3 percentage points, to stop hazardous work.

- Children living with at least one biological parent are more likely, by around 4 percentage points, to stop hazardous work.

- Children who have older siblings are less likely, by around 2 percentage points, to stop hazardous work.

- The presence of a primary school in the community increases the likelihood that children stop hazardous work by around 3 percentage points.

Other factors included in the regression do not have statistically significant effects. This does not mean that they are irrelevant, but rather that we cannot be sufficiently confident from the data whether and by how much they affect the likelihood that children stop hazardous work under the CLMRS.

What we conclude and recommend

The data points to a number of factors which make it less likely that a child can be stopped from doing hazardous work. The factors are broadly in line with empirically established risk factors for child labour more generally. If children are in child labour and also out of school, not living with their biological parents (e.g. children living with relatives or adopted children), have older siblings or do not have access to a primary school in the community, these children will need extra attention and effort for remediation. If a CLMRS identifies cases of child labour coupled with one or more of these risk factors, it should have a mechanism to flag these cases to ensure that these children receive appropriate remediation and are followed up closely.

It is important to note however that these factors are associated with the likelihood of children stopping hazardous work, but they may not necessarily reveal a causal effect on the success of the CLMRS. Conclusions about causal relationships between the chance that a CLMRS stops children from hazardous work and any of these factors require (quasi-) experimental methods which have not yet been applied in the specific context of CLMRS.

Box 3 presents an example of how data collected under PMI’s CLMRS in the tobacco sector has been triangulated with data from other sources to better understand root causes of child labour use and obstacles to addressing it, as well as to improve awareness-raising messaging accordingly.

- The likelihood that children stop doing hazardous work in response to remediation support received under the CLMRS changes according to contextual factors.

- Specifically, the likelihood of stopping hazardous work is higher for girls than for boys, for children who were in school at the time they were identified in child labour, for children living with at least one biological parent (as opposed to children living with relatives or adopted children, for example), for children who do not have older siblings and for children living in a community with a primary school present.`

- Even if some of these factors are not causal, they indicate which children will need extra attention and efforts for remediation. A CLMRS might apply a mechanism to flag these cases to ensure that they receive appropriate remediation and are followed up closely.

Under its Agricultural Labour Practices (ALP) programme (for more details see Box 1), working conditions of farmers supplying tobacco to PMI are systematically monitored by field technicians. As a primary source of data, field technicians collect information during their farm visits to build farm profiles and register practices that are not aligned with the ALP Code standards, as well as remediation steps and action plans.

To make full use of this data, PMI has started triangulating it with information from other sources, such as external assessments and grievance mechanisms, to better understand some of the underlying causes of the labour rights issues. PMI recommends triangulating data emerging from the CLMRS with data provided

by community structures, workers’ or farmers’ associations, other civil society organisations and government, in order to build a full picture of the reality on the ground and the main risks. Concretely, the data that is collected from external assessments and from public sources is used internally, to quantify the potential risk of child labour that may not be captured by the farm by farm monitoring (given that field technicians are only present on the farms for a limited amount of time and the issues identified are often systemic).

On the other hand, PMI combines qualitative data (collected through participatory methods) to assess the effectiveness of initiatives on the ground and their impact on addressing the root causes of child labour. A representative example is the external verification performed in Indonesia. One of the key findings

is that child labour is seen as part of a widespread societal norm of communal work (gotong royong). Strong cultural beliefs ingrained in the society, including those held by some local leaders, educators and community representatives, potentially weaken the company’s messaging about child labour. This insight reinforced PMI’s understanding of the root causes of child labour, leading them to introduce and redesign initiatives including training and awareness-raising.

How do different types of remediation support perform in comparison, in terms of stopping children from doing hazardous work?

- Data from follow-up visits to children previously identified in hazardous child labour under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

Child has stopped doing hazardous work: a child previously identified in child labour has claimed to no longer be doing hazardous work during two consecutive follow-up visits.

Types of remediation: See Appendix A for an overview and description of types of remediation provided under CLMRS in the cocoa sector.

Sequences of follow-up visits available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire. The validity of results for other contexts may be limited.

An appropriate remediation type is typically chosen for each child based on the child’s profile and specific needs, which, as such, drive chances for a child to stop hazardous work. Therefore, the relationship we observe between receiving a certain remediation type and stopping hazardous work is not necessarily causal.

Definition:

- In the context of a CLMRS, support is provided to children in and at risk of child labour to prevent, mitigate and remediate child labour.

- Remediation support includes activities to prevent future child labour cases and remediate current child labour cases. It can include the provision of assistance (e.g. in obtaining a birth certificate), services (e.g. tailored awareness-raising) or goods (e.g. school kit), and can be provided at the child, household or community level.44

The method we use

We examine how the chance of a child stopping hazardous work is associated with the type of remediation support the child (or the child’s family or community) received under the CLMRS. We use sequences of follow-up visits under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.45 As in previous sections, we define “having stopped hazardous work” as a child previously identified in hazardous child labour not having done hazardous tasks for at least two consecutive follow-up visits. For obvious reasons, we also consider for this analysis only remediation services the child received before the relevant follow-up visit took place.

We use a logit regression model specified as follows:

Units of observation are children previously identified in hazardous child labour.

The dependent variable is whether a child has stopped doing hazardous work.

The explanatory variables of interest are indicators of whether the child has received a certain type of remediation, taking into account that many children have received more than one type of remediation.

As control variables we include:

the child’s age and sex (unless we split the sample by sex)

whether the child was enrolled in school at the time they were identified in hazardous child labour

whether the child is living with at least one biological parent

whether the child has older siblings

the number of children living in the household

whether the head of household and the spouse of the head of household can read and write

whether the household is headed by a woman

the age of the head of household (as a linear and a squared term to allow for a non-linear relationship)

whether there is a primary school in the community (unless we split the sample by primary school presence)

whether the community is accessible by road all year round

whether the community is connected to the electricity grid

In order to better understand which remediation type has been most effective in which situation, we split the sample of children into groups: we look separately at boys and girls; at children aged 5 to 12 years (primary school age) and 13 to 17 years; and at children living in communities where a primary school is present, as opposed to in ones where no primary school is present.

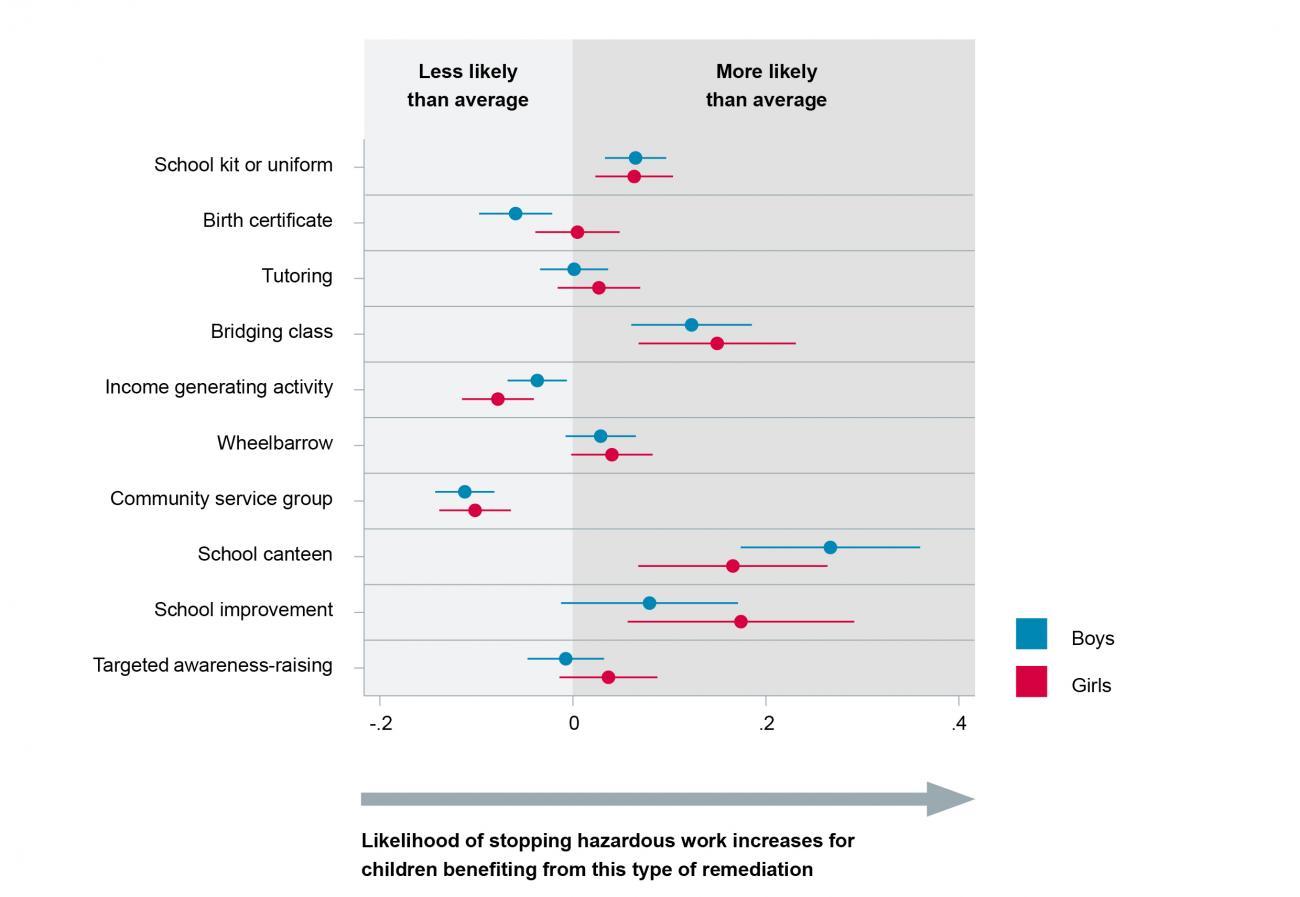

What we find

Overall, we see that remediation types aimed at improving school access and school quality appear to be particularly effective at stopping children from doing hazardous work. When children benefit from school canteens or other improvements to schools within the community, when they have access to bridging classes and when they are provided with school kits or uniforms, they are particularly likely to stop hazardous work.46 Living in communities where Community Service Groups47 have been put in place or in families which receive support for income generating activities, is associated with a below-average likelihood of stopping hazardous work. In interpreting these results, we should take into account that for Community Service Groups, we have information only on whether a Community Service Group has been set up in the child’s community, but not by whom the group’s labour services have been requested. Similarly for income generating activities, we have information only on whether such support has been received by a household, but not on whether additional income has indeed been generated as a result.

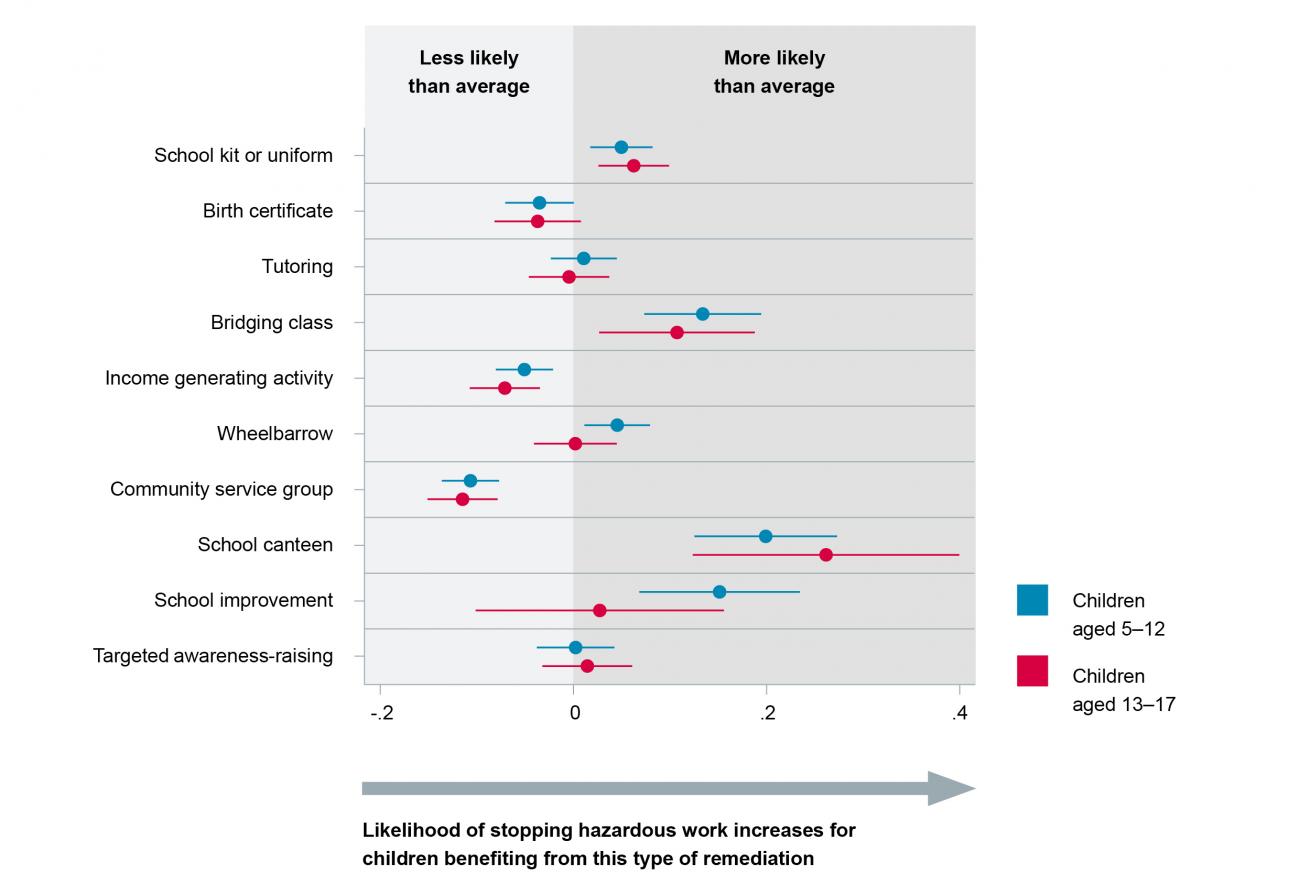

We see only minor differences between girls and boys for most types of remediation. However, there are a few exceptions: notably the provision of birth certificates, school improvements (which include, for example, the installation of toilets), bridging classes, tutoring and awareness-raising, from which girls seem to benefit more than boys. On the other hand, boys seem to benefit more from school canteens.

Figure 12 illustrates how strongly the different remediation types are associated with the likelihood of girls (red dots) and boys (blue dots) stopping hazardous work (after separating out the effects of other types of remediation received by the same child, as well as effects of child, household and community characteristics). Dots located further to the right indicate remediation types associated with a higher likelihood that children stop hazardous work (the dots represent marginal effects from the logit regressions specified above; see notes below the graph for full details).

Figure 12: By how much does the likelihood of stopping hazardous work increase for beneficiaries (boys versus girls) of different remediation types?

Notes: Marginal effects from a logit regression where the dependent variable is whether or not a child has stopped doing hazardous work, and the main explanatory variables are indicators for having received different types of remediation. For example, receiving a school kit or uniform has a marginal effect of approximately 0.07 for both boys and girls, indicating that for a recipient of a school kit or uniform, the likelihood of stopping hazardous child labour increases by approximately 7 percentage points, all other factors held equal. The value zero on the scale represents the average likelihood of a beneficiary stopping hazardous work, which is about 28% in this sample. All regressions also control for the child’s sex and age, school enrolment at time of first visit, total number of children in household, whether the child has older siblings, whether the child is living with biological parents, whether the head of household and spouse are literate, age of the head of household (simple and squared), electricity access and primary school presence in the community. Coefficient estimates displayed only for remediation types with reasonably large samples of beneficiaries (while in the actual regressions, we included all types of remediation). Dots indicate coefficient estimates, horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for these estimates (note that the confidence intervals tend to be larger the smaller the number of beneficiaries of a given remediation type in the sample). Data source: ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d'Ivoire.

Figure 13 shows differences between younger children (5–12 years) and older children (13–17 years) who receive different types of remediation. Overall, the likelihood of stopping hazardous work differs insignificantly between younger and older recipients of the various types of remediation (always relative to the average likelihood of stopping hazardous work within the age group, which as we know is higher for younger children). Only for improvements to schools does the data suggest that younger children might benefit more (even though the number of beneficiaries in both age groups in the sample is small, so that the difference is statistically not significant).

Figure 13: By how much does the likelihood of stopping hazardous work increase for recipients (in the 5–12 or 13–17 age group) of different remediation types?

Notes: Marginal effects from a logit regression where the dependent variable is whether or not a child has stopped doing hazardous work, and the main explanatory variables are indicators for having received different types of remediation (see also figure 12). All regressions also control for the child’s sex and age, school enrolment at time of first visit, total number of children in household, whether the child has older siblings, whether the child is living with biological parents, whether the head of household and spouse are literate, age of the head of household (simple and squared), electricity access and primary school presence in the community. Dots indicate coefficient estimates, horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for these estimates. Data source: ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d'Ivoire.

These results must be read as descriptive. They indicate which types of remediation are associated with higher rates of “success”, which is a combination of how effective a type of remediation is and of how difficult it is to address the child labour situation.

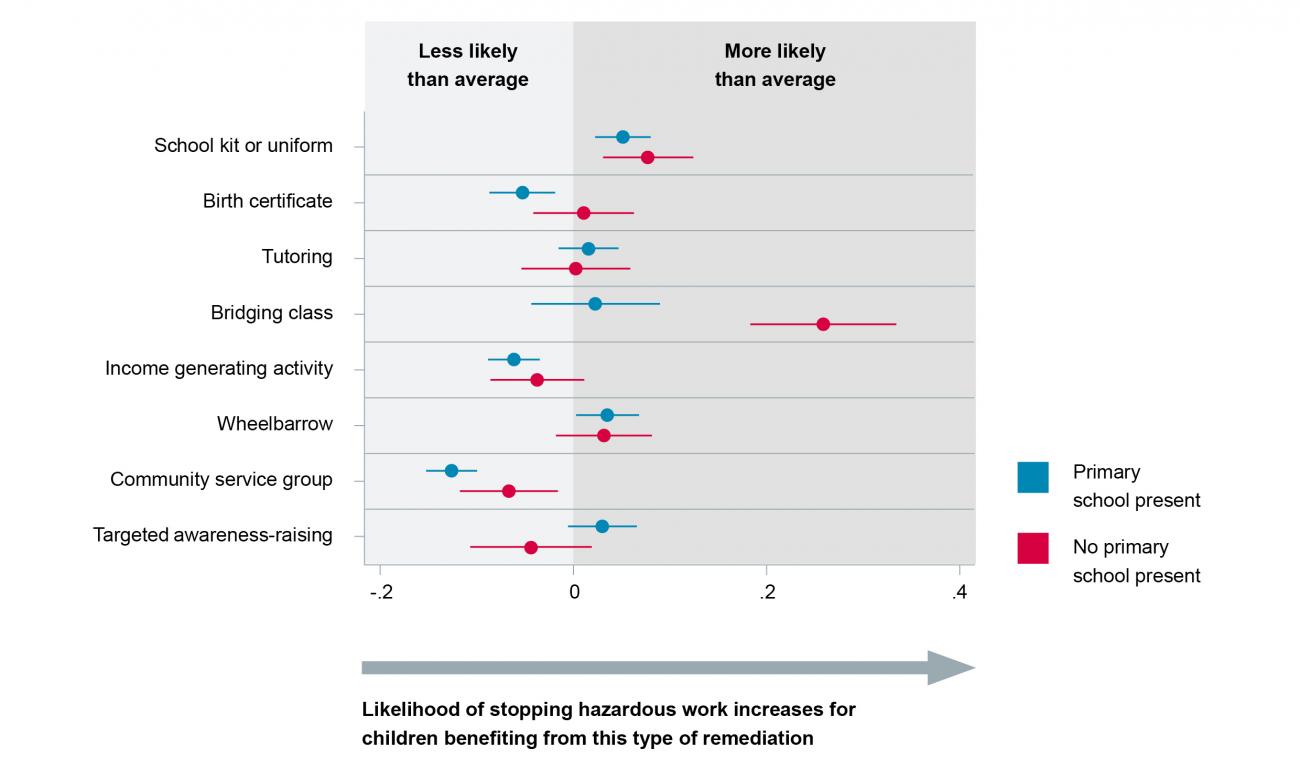

Figure 14: By how much does the likelihood of stopping hazardous work increase for beneficiaries living in communities with or without primary school of different remediation types?

Notes: Marginal effects from a logit regression where the dependent variable is whether or not a child has stopped doing hazardous work, and the main explanatory variables are indicators for having received different types of remediation (see also figure 12). All regressions also control for the child’s sex and age, school enrolment at time of first visit, total number of children in household, whether the child has older siblings, whether the child is living with biological parents, whether the head of household and spouse are literate, age of the head of household (simple and squared), electricity access in the community. Dots indicate coefficient estimates, horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for these estimates. Data source: ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d'Ivoire.

Finally, figure 14 breaks the sample down by whether a child lives in a community with or without a primary school present.48 One remarkable difference between these two contexts is that bridging classes are associated with a considerably higher likelihood that children stop hazardous work in communities with no primary school present, probably because they substitute for formal schooling in these communities. On the other hand, targeted awareness-raising is associated with a higher likelihood of stopping hazardous work in communities with a primary school, which may be because it is much easier in these communities to shift priorities towards children’s schooling and away from helping with farm work, in response to awareness-raising.

In interpreting the results above, we must take into account a few important points:

In our sample of remediation beneficiaries under the ICI CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, some types of remediation occur in large numbers, but others are much less common. Hence, we find strong evidence of effectiveness for some types of remediation, while for others we have insufficient data to draw conclusions. In the results presented above, we have excluded the least common remediation types, but even amongst the types presented, case numbers differ widely (larger confidence intervals, represented as horizontal bars in the graphs, indicate fewer cases).

The majority of children identified in hazardous child labour received more than one type of remediation (see Appendix E for details – in fact, 87% of the children in the sample benefited from at least two different types of remediation, while 29% even received four or more different types). To understand the effectiveness of individual remediation types, we “control for” (i.e. separate out the effect of) other remediation types in our regression model. These estimation results are obviously less precise than if we had experimental data on children having received only one specific remediation type.

Under ICI’s CLMRS model, the choice of remediation type in each case is made based on the child’s, household’s or community’s profile and specific needs (see online appendix for more details). The same factors which guide the choice of remediation type, however, also drive the inherent likelihood that the case can be resolved (e.g. children suffering multiple deprivations may be more likely to get support for birth certificates, but less likely to stop hazardous work; children living in remote communities are less likely to stop hazardous work, but more likely to benefit from school improvements; when parents sign up for literacy training, we may assume that they also have higher than average educational aspirations for their children). While the regression model above separates out effects of some of these drivers (see list of control variables), several unobserved factors may still bias the results. For conclusive evidence of the impact of the different remediation types one by one, we would have to draw on experimental research, which to our knowledge has not been conducted in the context of CLMRS projects in the cocoa sector.

These results must be read as descriptive. They indicate which types of remediation are associated with higher rates of “success”, which is a combination of how effective a type of remediation is as such and of how difficult to address the child labour situation is in which this remediation is frequently chosen (beyond the factors we can control for in the analysis).

What we conclude and recommend

Keeping in mind the limitations mentioned above, we draw the following broad conclusions:

Next to awareness-raising, support for access to and improving quality of schools appears to be particularly effective: these types of remediation are associated with a higher than average likelihood that beneficiaries stop hazardous work (whereby, on average, all types of remediation help to stop beneficiaries from hazardous work). This might reflect the fact that better schools increase returns from regular school attendance, even for children who previously combined school and work. Scaling up school-related interventions seems to be a promising way forward to address child labour.

Most remediation types appear to be similarly effective for girls and boys, with some exceptions: provision of birth certificates, school improvements, bridging classes, tutoring and awareness-raising, where the likelihood of girl recipients stopping hazardous work increases by more than that of boys.

Most remediation types appear to be similarly effective for children of different age groups, except school improvements, where the likelihood stopping hazardous work increases more amongst younger (5–12 years old) than amongst older (13–17 years old) beneficiaries.

Targeted awareness-raising is associated with a higher likelihood that children stop hazardous work in communities with a primary school present. In line with what we would expect, awareness-raising about the risks posed by child labour and the importance of schooling is most effective in combination with access to schooling.

More solid evidence is needed on impacts of the various remediation types, including the exact magnitude of effects, to inform cost-benefit analyses of remediation under CLMRS, with a view to increasing the cost-effectiveness of the systems. Such evidence is best generated by experimental research, where selected children in child labour are given a certain type of support in a controlled environment. Cost-benefit analysis of remediation types will help increase the cost-effectiveness of the systems and help scaling up.

- We look at how different types of remediation given to child labourers are associated with the likelihood that they stop hazardous work. The results are purely descriptive because the CLMRS allocates remediation types to children based on their needs and profiles.

- Overall, the results suggest that interventions to improve access to and quality of education are a promising remediation strategy under CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

- The data suggests that birth certificates, school improvements, bridging classes, tutoring and awareness-raising might be more effective for girls than for boys (in the context of ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire), while school improvements might be more effective for younger children.

- More solid evidence concerning the impacts of the various remediation types, including the exact magnitude of effects, is needed to inform cost-benefit analyses of the effectiveness of different remediation types under CLMRS.

How do different types of school-related remediation perform in comparison, in terms of increasing school participation?

- Data from follow-up visits to children previously identified in hazardous child labour under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Child has started participating in school: a child previously identified in child labour and out- of-school has been attending school during two consecutive follow-up visits.

- Types of remediation: see Appendix A for an overview and description of types of remediation provided under CLMRS in the cocoa sector.

- Sequences of follow-up visits available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire. The validity of results for other contexts may be limited.

- An appropriate remediation type is typically chosen for each child based on the child’s profile and specific needs, which in turn drive chances for the child to participate in school; this compromises the causal interpretation of the results.

The method we use

To complement the comparative analysis of different remediation types, we now look at how different types of school-related remediation perform in terms of helping out-of-school children to participate in school. We examine the likelihood that a child labourer initially out of school will start attending school, depending on which school-related remediation the child has received. As in the previous section, we use sequences of follow-up visits under ICI- implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.49 We consider an out-of-school child to have started going to school if the child has reported attending school during two consecutive follow-up visits.

We use a logit regression model specified as follows:

Units of observation are children previously identified in hazardous child labour and as out of school.

The dependent variable is whether a child has started participating in school, confirmed by two consecutive follow-up visits.

The explanatory variables of interest are indicators whether the child has received each of the school-related remediations, namely:

school kit or school uniform provided

birth certificates provided

participation in tutoring

participation in bridging class

school built in the community

improvement of school in the community

school in the community equipped with a school canteen

- As control variables we include:

- the child’s age and sex (unless we split the sample by sex)

- whether the child was enrolled in school at the time they were identified in hazardous child labour

- whether the child is living with at least one biological parent

- whether the child has older siblings

- the number of children living in the household

- whether the head of household, and whether the spouse of the head of household can read and write

- whether the household is headed by a woman

- the age of the head of household (as a linear and a squared term to allow for a non-linear relationship)

- whether there is a primary school in the community (unless we split the sample by primary school presence)

- whether the community is accessible by road all year

- whether the community is connected to the electricity grid

In order to better understand which school-related remediation type has been most effective in which situation, we split the sample of children into groups as we did in the previous section. We look separately at boys and girls; at children aged 5 to 12 years (primary school age) and 13 to 17 years; and at children living in communities where a primary school is present and in ones where no primary school is present.

What we find

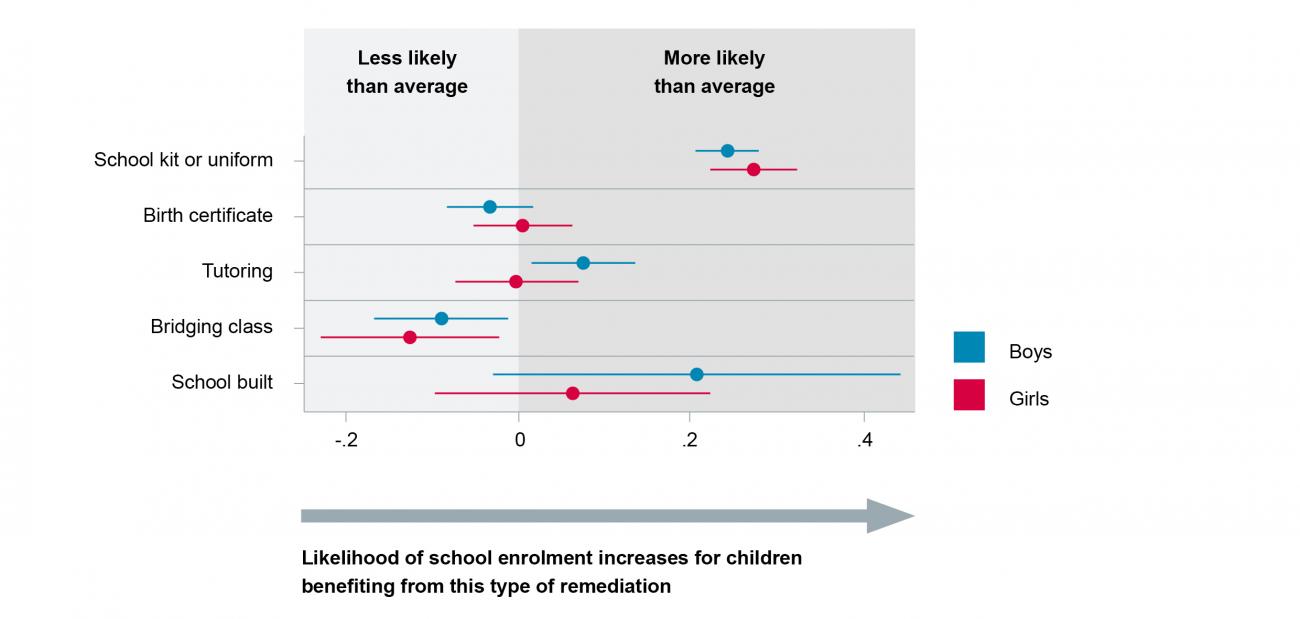

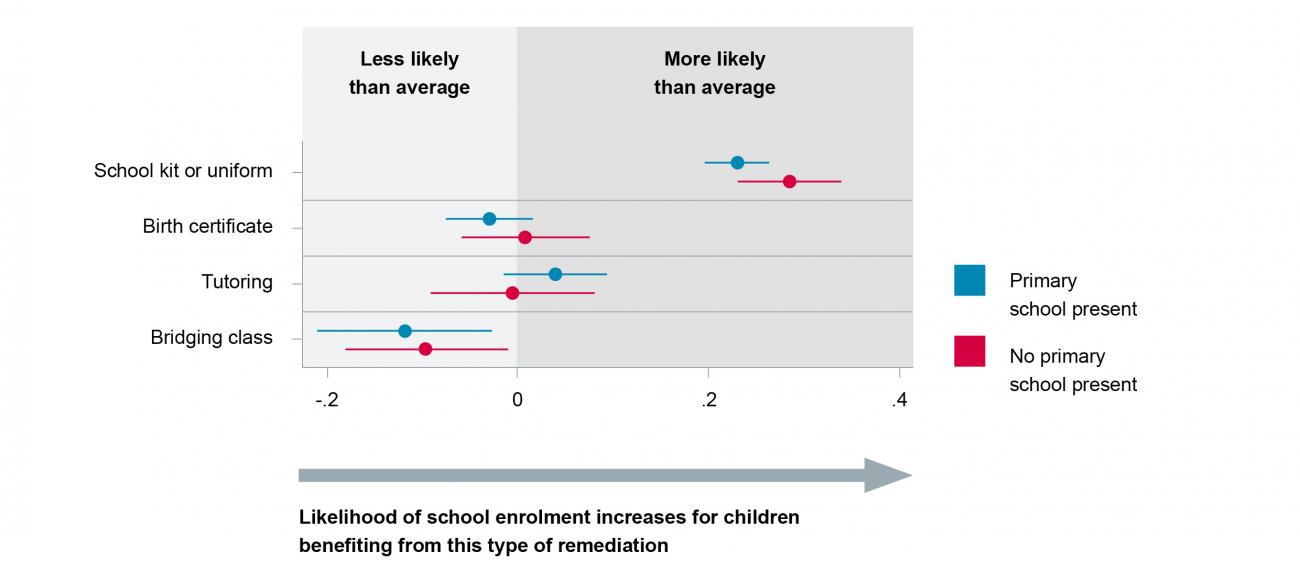

Figure 15 illustrates how strongly the different school-related remediation types are associated with the likelihood of girls (red dots) and boys (blue dots) starting to participate in school (after separating out the effects of other school-related remediations received by the same child, as well as effects of child, household and community characteristics). Dots located further to the right indicate remediation types associated with a higher likelihood that children start participating in school (the dots represent marginal effects from the logit regressions specified above; see notes below the graph for full details). Effects are only reported for intervention types with reasonably large numbers of out-of school children in the sample (which is not the case for school improvements and school canteens).

We can see that the likelihood that children start participating in school is highest for provision of school kits and uniforms, by a similar magnitude for boys and girls. Of the interventions analysed here, the only one which appears to be slightly more effective for girls than for boys is birth certificates. For tutoring, bridging classes and building schools, the data suggests that boys might benefit more than girls, but none of these differences is statistically significant.

Figure 15: By how much does the likelihood of starting to participate in school increase for boys or girls receiving different types of school-related remediation?

Notes: Marginal effects from a logit regression where the dependent variable is whether a child has started going to school, and the main explanatory variables are indicators for having received different types of school-related remediation. For example, receiving a school kit or uniform has a marginal effect of approximately 0.24 for boys, indicating that receiving a school kit or uniform increases the likelihood that the boy starts going to school by 24 percentage points, all other factors held equal. The value zero on the scale represents the average likelihood for a beneficiary to start going to school, which is about 14% in this sample. All regressions also control for the child’s sex and age, school enrolment at time of first visit, total number of children in household, whether the child has older siblings, whether the child is living with biological parents, whether the head of household and spouse are literate, age of the head of household (simple and squared), electricity access and primary school presence in the community. Coefficient estimates displayed only for remediation types with reasonably large samples of beneficiaries (while in the actual regressions we included all types of school-related remediation). Dots indicate coefficient estimates, horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for these estimates (note that the confidence intervals tend to be larger the smaller the number of beneficiaries of a given remediation type in the sample).

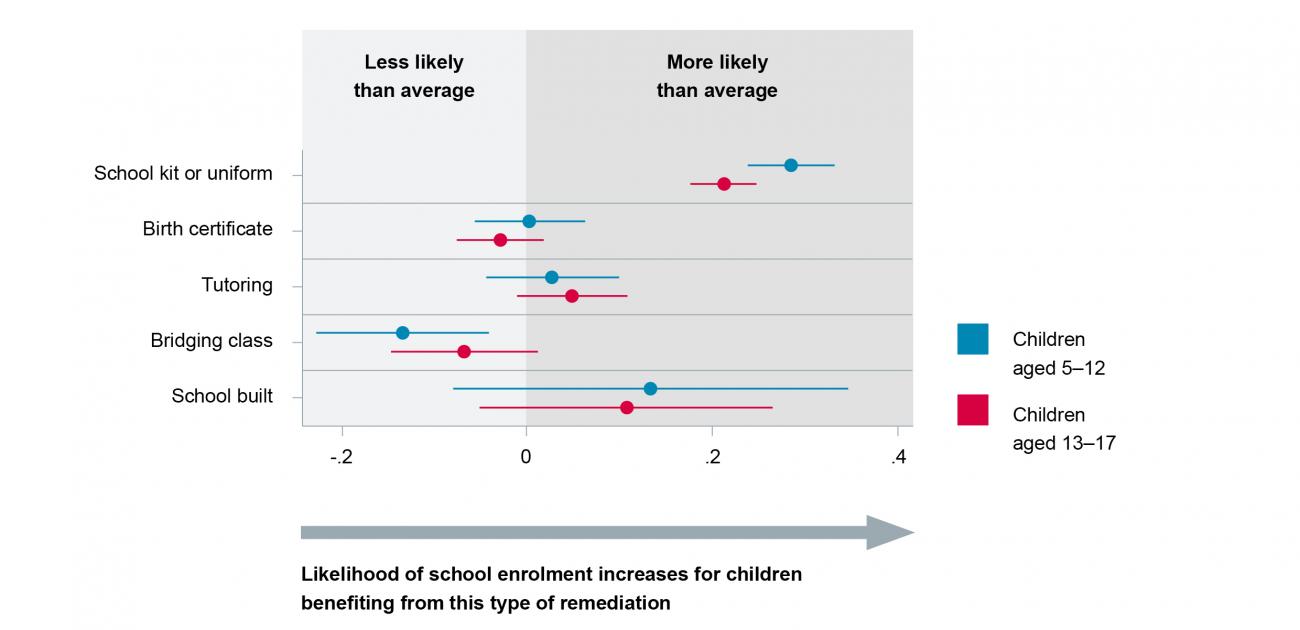

When we break the sample down by age groups (figure 16), the data suggests that school kits are slightly more effective for children of primary school age. Interestingly, the same is true for birth certificates (but the difference is not statistically significant), even though in theory birth certificates enable access to secondary schooling. A possible explanation for this is that motivation for primary school enrolment increases if children have perspectives for continuing school at a higher level.

Figure 16: By how much does the likelihood of enrolment in school increase for beneficiaries (aged 5–12 years or 13–17 years) of different school-related remediation types?

Notes: Marginal effects from a logit regression where the dependent variable is whether a child has started going to school, and the main explanatory variables are indicators for having received different types of school-related remediation. All regressions also control for the child’s sex and age, school enrolment at time of first visit, total number of children in household, whether the child has older siblings, whether the child is living with biological parents, whether the head of household and spouse are literate, age of the head of household (simple and squared), electricity access and primary school presence in the community. Coefficient estimates displayed only for remediation types with reasonably large samples of beneficiaries (while in the actual regressions we included all types of school-related remediation). Dots indicate coefficient estimates, horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for these estimates. Data source: ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d'Ivoire

Finally, we break the sample down by whether children are living in a community with a primary school present or with no primary school present (figure 17). The graph includes only effects for types of intervention which are provided in communities with and without primary schools present. The data suggests that birth certificates are more effective in contexts where no primary school is present within the community (but this difference is not statistically significant), while for the other types of intervention, the presence of a primary school does not strongly affect their relevance.

Figure 17: By how much does the likelihood of starting to participate in school increase for children living in communities with or without a primary school present, who receive different types of school-related remediation?

Notes: Marginal effects from a logit regression where the dependent variable is whether a child has started going to school, and the main explanatory variables are indicators for having received different types of school-related remediation. All regressions also control for the child’s sex and age, school enrolment at time of first visit, total number of children in household, whether the child has older siblings, whether the child is living with biological parents, whether the head of household and spouse are literate, age of the head of household (simple and squared), electricity access and primary school presence in the community. Coefficient estimates displayed only for remediation types with reasonably large samples of beneficiaries (while in the actual regressions we included all types of school-related remediation). Dots indicate coefficient estimates, horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for these estimates. Data source: ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d'Ivoire

What we conclude and recommend

For reasons discussed in detail in the previous section, these results are purely descriptive. They indicate which types of school-related remediation are associated with higher rates of “success” in terms of children participating in school, which is a combination of how effective a type of remediation is as such and of how persistent the obstacles to a child’s school participation are (beyond the factors we can control in the analysis).

Keeping this in mind, we draw the following broad conclusions:

As a general observation, remediation planning should take into account that different remediation types are effective in relation to different objectives. While some remediation types may not be the most effective at stopping children from hazardous work, they may improve children’s situations by facilitating school participation and lead to better learning and development outcomes (although it goes beyond the scope of CLMRS data collection to measure a broader range of outcomes).

Provision of school kits or uniforms is associated with an increased likelihood that beneficiaries start participating in school, probably because it helps to overcome some of the financial barriers to school attendance for poor households. This is also the school-related remediation type which is rolled out at largest scale.

The data does not suggest any clear differences in effects between boys and girls, children of different age groups or communities with or without a primary school present.

More data is needed to assess how effective community or school level interventions are in terms of bringing out-of-school children to school. The data used here are limited to children in child labour and followed up under the CLMRS, while the community- and school-level interventions reach a much larger group of children, including children who are not in child labour.

These results show that different types of remediation should be evaluated in terms of different child outcomes.

If a remediation seems to have a relatively weak effect in terms of stopping children from hazardous work, it may nonetheless have a strong effect in terms of bringing children to school. This is the case, for example, for the building of new schools in communities. An example of the opposite effect is bridging classes, which relative to other types of remediation are highly effective in terms of stopping children from doing hazardous work, but are less effective at encouraging participation in regular schools, relative to other remediation types.

We have also analysed the effectiveness of two more specific types of interventions on specific intended outcomes, namely:

- the effect of a parent’s participation in literacy classes on children’s school enrolment

- the effect of providing a wheelbarrow to a household on children’s engagement in carrying heavy loads above the permissible weight.

In neither case could we find statistically significant effects for these intervention types on the intended outcomes in the framework of this analysis. There are several possible explanations why the data does not reveal specific effects of these specific interventions, e.g. because parents interested in literacy classes may already be more likely to send their children to school or because these types of interventions are in many cases combined with others, so that it becomes difficult to attribute effects to specific elements of support. For more solid evidence on the effectiveness of specific remediation types on specific outcomes, focused studies with experimental methods are required.

- We look at how different types of school-related remediation given to out-of-school children in child labour are associated with the likelihood that these children start participating in school. The results are purely descriptive because the CLMRS allocates remediation types to children based on their needs and profiles.

- The results suggest that the provision of school kits and school uniforms is a promising strategy for increasing school participation amongst child labourers under CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

Different types of remediation show different results depending on the outcome we look at. Remediation types which appear relatively less effective in terms of stopping children from hazardous work may be effective in terms of increasing their school participation and vice versa.

- More comprehensive data (not limited to follow-up records of child labourers) and robust methods of assessment are needed to understand the effectiveness of interventions at school level.

References

39 Sequences of follow-up visits to a sufficient number of children were available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, which have been in place for several years and use a data management system which allows the tracking of individual children.

40 How much time elapses after a child has been identified in child labour until the child receives a remediation depends on the local context: if the child’s circumstances allow, ICI technical agents wait for data from a critical number of children from the same community coming in to select an appropriate remediation service and allow for collective delivery.

41 For hours and days worked on hazardous tasks, the questions are asked differently when the household is first visited to identify any potential cases of child labour than during follow-up visits to children previously identified in hazardous child labour.

42 We also include here only cases of child labour identified after August 2018, which is when the government of Côte d’Ivoire revised the list of hazardous tasks.

43 Sequences of follow-up visits to a sufficient number of children were available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, which have been in place for several years and use a data management system which allows the tracking of individual children.

44 ICI (2021) Benchmarking Study: Overview and Definition of Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems.

45 Sequences of follow-up visits to a sufficient number of children were available for this review only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, which have been in place for several years and use a data management system which allows the tracking of individual children.

46 However, the effects of school-level interventions are estimated with the lowest precision (see the large confidence intervals), given that the numbers of beneficiaries in the sample are relatively small.

47 A Community Service Group is a group of trained and equipped adult labourers, often youth, who provide services, such as spraying agrochemicals or land clearing, at an affordable price or sometimes even for free.

48 We do not include in this comparison school-level interventions which are not relevant for communities with no primary school present, or, conversely, where a primary school present, such as school canteens, the building of new schools and improvements to school buildings.

49 Sequences of follow-up visits to a sufficient number of children were available for this review only from ICI implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, which have been in place for several years and use a data management system which allows tracking of individual children.