This study provides an in-depth analysis of data from Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems (CLMRS) from cocoa-growing areas of West Africa. It aims to answer two questions: 1) How does the design and set-up of these systems affect their ability to identify cases of child labour? 2) How effective are these systems at protecting children from hazardous work?

What is a Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation System?

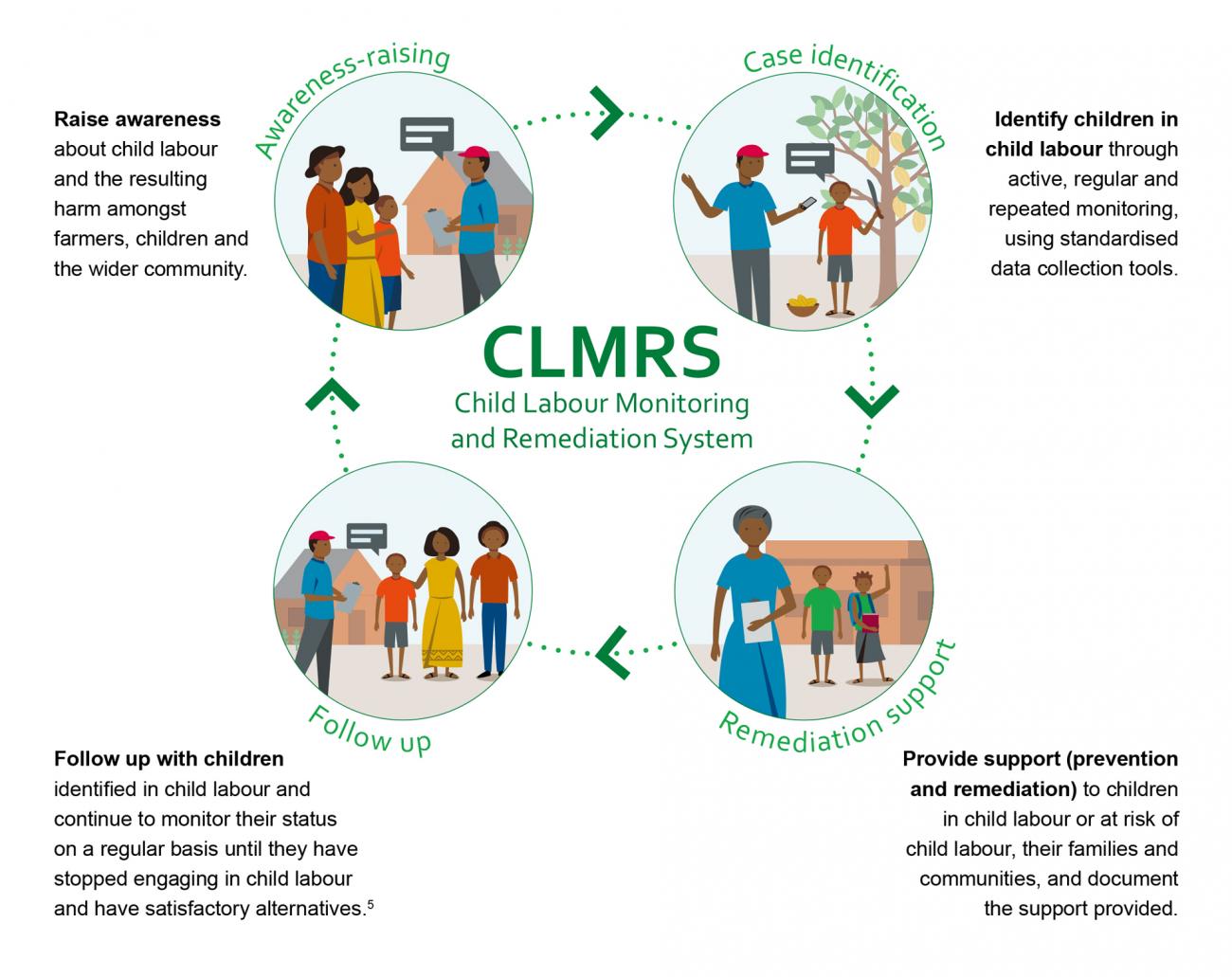

Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems (CLMRS) represent a means of targeting prevention, mitigation and remediation assistance to children involved in or at risk of child labour, as well as to their families and communities.

The concept of Child Labour Monitoring was initially developed in the 1990s by the International Labour Organization (ILO), as part of its International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour:

“The immediate goal of child labour monitoring is to identify and remove girls and boys from child labour. It is an active process that involves regular, ongoing direct observations to identify child labourers and determine risks to which they are exposed. It also includes referring children to services, verifying that they have been removed and tracking them afterwards to ensure that they have satisfactory alternatives.”1

Since 2005, the ILO’s Guidelines for Developing Child Labour Monitoring Processes have come to serve as the basis for developing and implementing systems to monitor child labour in a wide variety of geographic contexts and across supply chains. In West Africa’s cocoa sector, where child labour is a persistent human rights concern, CLMRS are increasingly being promoted by a range of stakeholders, including governments, certifiers, companies and membership organisations. Moreover, several stakeholders have recently made commitments to scale up these systems significantly across the entire cocoa supply chain.2

One factor that may have contributed to the increasing adoption of such monitoring systems is their use as a due diligence tool. The 2011 UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights sets out the responsibility of businesses to put in place “a human rights due diligence process to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their impacts on human rights” and to “enable the remediation of any adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which they contribute”.3 A raft of legislation that has been adopted or is currently being drafted in various countries is making human rights due diligence mandatory for businesses operating global supply chains. In contexts where the use of child labour in agricultural production is recognised as a salient human rights risk – as is the case in the cocoa sector – increasing numbers of businesses are using CLMRS to conduct due diligence.

The overall aim of the study is to identify ways of improving the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems, as a means of supporting ongoing efforts to scale them up.

In this review, we use an operational definition of Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems (as set out in a benchmarking study previously conducted by ICI), according to which they must include the following core activities:4

Wherever possible, all these core activities should be implemented alongside structures already in place to address child labour, especially government systems, and at the same time seek to strengthen them. They should also pursue capacities building of all local stakeholders involved in the system. Outcomes should be independently verified by third parties.

Objectives, scope and structure of this review

In this study, we examine several child labour monitoring and remediation systems currently in place in the West African cocoa sector. Our aim is to identify ways of improving the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of these systems, as a means of supporting ongoing efforts to scale them up. Building on the 2017 Effectiveness Review of Child Labour Monitoring Systems in the Smallholder Agricultural Sector of Sub-Saharan Africa,6 this second-phase study was able to adopt a more detailed approach that made use of data from systems implemented in a range of different contexts and using different modalities. We analysed data from a total of 12 CLMRS projects, in order to understand how differences in their design, set-up, operation and management affect their functioning. We draw on these insights not in order to recommend a single approach or to propose a ‘gold standard’ for such monitoring systems, but rather to highlight the variety of approaches that have been adopted, as well as to compare, wherever possible, their effectiveness using a range of different criteria. In this context, the study aims to answer two main questions:

- How does the design of specific components affect a child labour monitoring and remediation system’s overall ability to identify cases of child labour?

- How effective are these systems and the different types of support provided when it comes to protecting children from hazardous work and improving their access to education?

Our focus here is primarily on those elements that could be examined on the basis of the quantitative data provided by the participating stakeholders.

The analysis is divided into two parts: Part A addresses the question of how effective the different systems are at identifying cases of child labour, using data obtained from monitoring visits. Part B addresses the question how effective the different systems are at reducing children’s exposure to hazardous work and increasing their participation in school, using data obtained from follow-up visits to children who have received support. Appendix A provides a detailed overview of the different systems currently in place in the cocoa sector while the online appendix contains additional details about the data and methods used, along with supplementary analytical results.

Data sources and methodology overview

In preparation for this review, ICI requested that participating stakeholders in the sector share two types of data:

- Key information about the system set-up, including the institutional set-up, implementing partners, coverage of farmers, details of data collection and the provision of support to farmers and their children.7

- Selected anonymised data from monitoring visits conducted at the child level (including basic demographic information, whether the child was identified as participating in child labour and whether they received any support).

In total, data from six stakeholders has been included in this review, albeit with some variation in the level of detail provided.

Data from monitoring visits is available from 12 CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, including seven implemented directly by ICI, two implemented with ICI support and three implemented independently of ICI. The compilation of this child-level monitoring data has enabled us to address questions related to the identification of child labour cases. More detailed information is available for ICI-implemented CLMRS, allowing us to raise further, more detailed questions concerning where and when visits take place, as well as the characteristics of monitoring agents.

Data on follow-up visits to children previously identified as participating in child labour (which were available only from systems at an advanced stage of implementation) is used to evaluate a given monitoring system’s success at improving children’s situation over time.

Key Recommendations

The main measures identified in this review that could improve the effectiveness of child labour monitoring systems include:

- Scheduling and adapting awareness-raising campaigns to match the seasonal patterns of certain hazardous tasks, thus improving their effectiveness by helping to increase perceived relevance and to prevent awareness-raising fatigue.

- Using a combination of household monitoring visits and farm visits to increase the likelihood that all cases of child labour are identified and can be addressed.

- When recruiting locally based monitors, making efforts to recruit and retain more female monitors, incentivise experienced monitors to stay in the job and set a minimum level of education for prospective monitors (secondary school, if sufficient candidates are available).

- Focusing extra attention and remediation efforts on out-of-school children, children not living with a biological parent (e.g., children living with relatives or adopted children), boys, older children and eldest siblings, as data suggests these are the hardest profiles to keep away from hazardous work.

- Verifying through multiple follow-up visits that a child has stopped hazardous work after having received remediation support. We recommend following up on children’s progress until they have no longer reported engaging in hazardous child labour for at least two consecutive follow-up visits, with a minimum three-month interval between the visits.

Data from monitoring visits is available from 12 CLMRS, including 7 implemented directly by ICI, 2 implemented with ICI support and 3 implemented independently of ICI.

References

- ILO (2005) Guidelines for Developing Child Labour Monitoring Processes, 66.

- See, for example, ICI Strategy 2021-26; WCF Strategy: Pathway to Sustainable Cocoa (2020). Most recently, in order to mark 2021 as the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour, ICI and its members have pledged to scale up system coverage.

- UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, 2011: 20-21.

- ICI (2021) Benchmarking Study: Overview and Definition of Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems.

- ILO (2005) Guidelines for Developing Child Labour Monitoring Processes.

- ICI (2017) Effectiveness Review of Child Labour Monitoring Systems in the Smallholder Agricultural Sector of Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Information concerning the cost of the systems was also provided by some stakeholders. However, this information refers to different elements in different systems, meaning that it could not be used for a comparative analysis. Such an analysis will be the subject of a follow-up study, once more consistent and complete information on system costs has been shared and compiled.