In this section

- What levels of child labour intensity do different CLMRS projects measure?

- How does child labour identification vary at different times of the year?

- How effective are different types of monitoring visits for identifying child labour?

- Which monitoring agents are more effective at identifying cases of child labour?

- References

This section examines the likelihood of identifying children in child labour through monitoring visits. It looks at how different elements of system design and implementation – including who conducts monitoring visits, when, where and how – relate to the likelihood that a system can identify cases of child labour, so that later these children can receive support.

How do child labour identification rates vary across projects?

- Descriptive comparison of child labour identification rates.

- Child labour identification rate: number of children identified in child labour, divided by the number of children interviewed during monitoring visits under a given CLMRS project.

- Comparability of results across CLMRS projects is compromised as monitoring visits take place under different circumstances.

The method we use

We compare the rates of hazardous child labour cases identified across various CLMRS projects in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. The rate of hazardous child labour identification is defined here as the number of children identified in hazardous child labour divided by the number of children interviewed during monitoring visits under a given CLMRS project. The data used is predominantly from first- time monitoring visits, which took place before the farmers and children interviewed received any support. We also compare the rates of hazardous child labour cases identified under CLMRS with the rates of hazardous child labour amongst cocoa farming households, as assessed through nationally representative surveys.

Child labour is work that “deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development.”25

Hazardous Child Labour is work that is “likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children” due to its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out.26 Hazardous Activity Frameworks, developed by national governments, list specific tasks that are considered as hazardous.

What we find

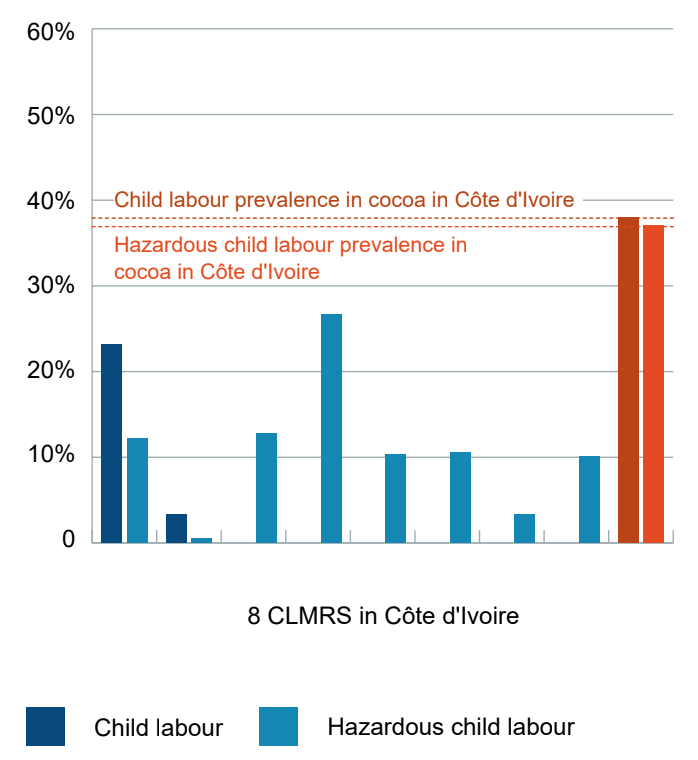

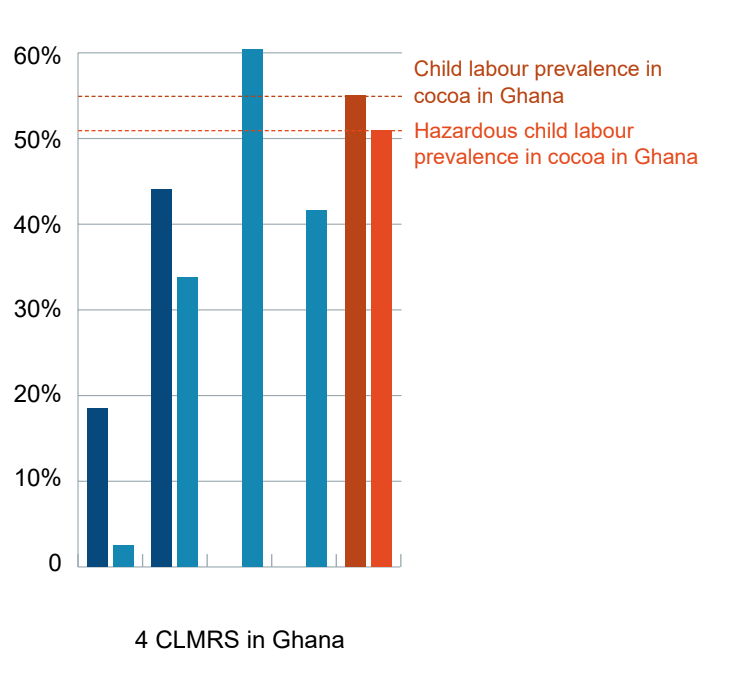

We find huge differences between CLMRS projects in how likely it is that a monitoring visit results in identification of a child labour case (see figure 1). The rates of hazardous child labour identification in projects in Côte d’Ivoire range between 0.5% and 26.7%, while in projects in Ghana they range between 2.5% and 60.4%. According to the CLMRS data we have available, monitoring visits in Ghana are more likely to identify cases of child labour than in Côte d’Ivoire.24 While this trend is consistent with findings from the Tulane and NORC surveys, in the context of CLMRS, it is partly explained by other factors not related to the country context, such as the modalities of data collection, as analysed in the following sections. There are however some common patterns, which are consistent with findings from survey research on child labour prevalence in cocoa production (e.g. NORC 2020): in almost all projects, boys are more likely to be identified in hazardous child labour than girls, and children above the age of 12 years are more likely to be identified in hazardous child labour than younger children.

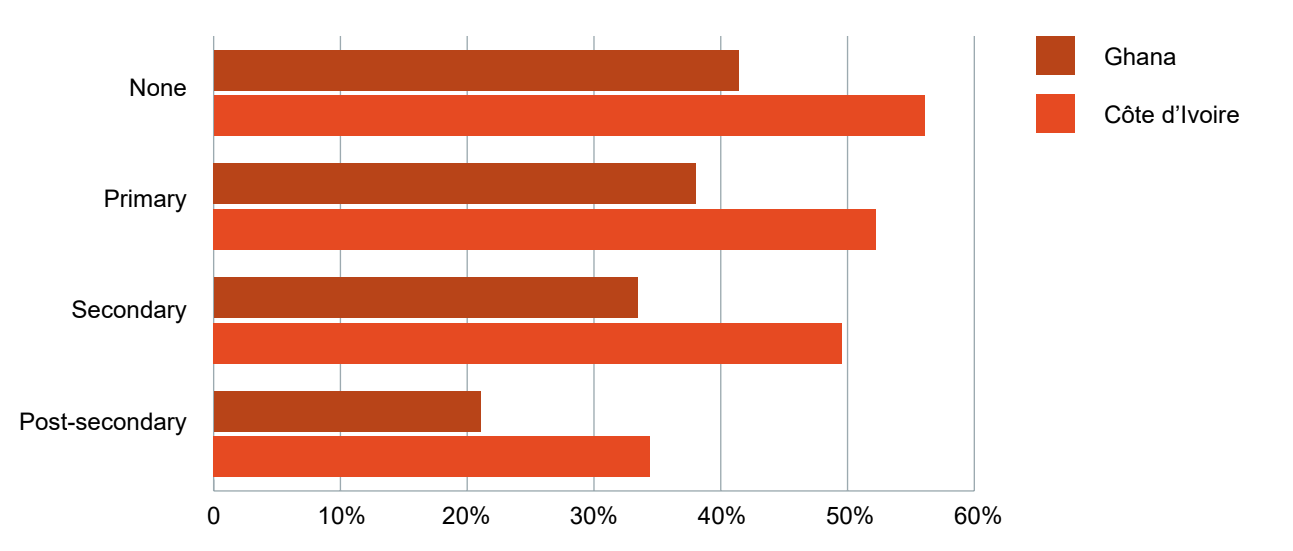

On average, the rates of hazardous child labour cases identified under CLMRS are substantially lower than the rates of child labour prevalence in cocoa production in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, according to the 2020 NORC Survey Report, which provides the best available estimates for the sector at the national level. It is of course possible that the true prevalence of child labour amongst households covered by CLMRS projects is indeed lower than the respective national average (e.g. due to differences in socio-economic profiles of farmers who are members of certified cooperatives or to differences across cocoa- growing areas). However, judging from the variation in child labour prevalence between socio-economic strata and between regions as measured by the 2018/19 NORC survey research (see figure 2 and table 2, which show differences between NORC sub-samples by father’s education, and by region), we would not expect the true child labour prevalence for CLMRS-covered farmers to deviate from the national average by as much as what we observe; and we would also not expect the differences between groups of farmers covered by different systems to be as marked as the observed differences in identification rates.

Figure 1a: Identification rates of child labour and hazardous child labour in 8 different projects in Côte d’Ivoire.

Figure 1b: Identification rates of child labour and hazardous child labour in 4 different projects in Ghana.

Notes:Child labour identification rates are defined as numbers of children identified in (hazardous) child labour, divided by numbers of children interviewed during monitoring visits. Data source: Compiled data from monitoring visits under 12 CLMRS projects in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. (Hazardous) child labour prevalence rates in agricultural households in cocoa growing areas of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana according to NORC (2000).

Table 2: Child labour prevalence rates within sub-samples of the 2018/19 NORC survey research data set, by father’s education (calculations by ICI).

Figure 2: Child labour prevalence rates within sub-samples of the 2018/19 NORC survey research data set, by region (calculations by ICI).

Côte d’Ivoire | Ghana | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Worodougou | 17.14% | Volta | 17.98% |

Agnéby-TiassaLac | 23.22% | Western | 47.07% |

Belier | 29.13% | Ashanti | 48.24% |

Lohdjiboua | 34.31% | Central | 52.72% |

Haut-Sassandra | 49.34% | Brong Ahafo | 57.41% |

Goh | 49.34% | Eastern | 62.11% |

Data source: NORC cocoa report data sets.

What we conclude and recommend

CLMRS data collection is guided by different objectives and different circumstances than sample- based survey research, which is designed to generate robust estimates of child labour prevalence. Under CLMRS, less time-consuming interviews with less elaborate questionnaires may be preferred because this allows more children to be monitored with a given budget.

While some systems are reasonably effective at identifying a significant proportion of child labourers, there is still room for improvement, with most CLMRS failing to capture all cases within the monitored farming households.

While each CLMRS has to find the right balance between how many children can be covered and how thorough each monitoring interview can be, CLMRS implementers should explore how to limit under-reporting of child labour. Options may include:

Making sure monitoring agents have an in-depth understanding of definitions and concepts of child labour.

Training monitoring agents more carefully in interview techniques with children.

Providing more intensive supervision, guidance and quality control in relation to the work of monitoring agents.

Improved data collection tools, including translation into local languages.

If under-reporting of child labour is due to a fear that households will lose certification or other benefits, awareness-raising might be adjusted to explain that monitoring is intended as a supportive rather than a punitive action.

Another option to improve the efficiency of child labour monitoring is to prioritise high-risk farmers for visits, based on a previous assessment of the household’s risk using readily available data. For a comprehensive overview of available methods for risk modelling and experience to date with risk- based child labour monitoring, see ICI’s recent overview paper.27

- CLMRS in the cocoa sector in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana perform very differently in terms of identifying cases of child labour.

- While some systems are reasonably effective at identifying a significant proportion of child labourers, there is still room for improvement, with most CLMRS failing to capture all cases

within the monitored farming households.

- CLMRS implementers should make continued efforts to revise and improve protocols for monitoring visits, data collection tools, messaging around CLMRS objectives and training and support for monitoring agents, to keep under-identification at a minimum level.

What levels of child labour intensity do different CLMRS projects measure?

Compiled data from monitoring visits under 12 CLMRS projects in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

Of the 12 CLMRS projects, 10 collect data on the number of hours children work in cocoa per day or per week.

- A descriptive comparison of outcomes measured across CLMRS projects.

- Number of hours a child has worked in cocoa over the course of one week: for children aged 10 years or older only (younger children are not able to provide sufficiently reliable estimates of time spent doing a certain activity).

- The comparability of results across CLMRS projects is compromised as monitoring visits take place under different circumstances across CLMRS projects, while different projects work with different data collection tools.

The method we use

For those children who are identified in child labour under the different CLMRS, we compare the median number of hours they have worked over the course of one week, as reported by the children themselves. This information is available for 10 out of the 12 CLMRS projects in our compiled data set. Even though this information is generally collected from all children between age 5 and 17, we include here only records from children aged 10 years or older. This is because it is generally difficult for children to provide reliable estimates of the time they have spent doing a certain activity during a given reference period, and even more so for younger children. Previous analyses of child labour data from other contexts done by ICI have shown that estimates of hours worked are much more plausible if reported by older children.28

What we find

The median number of hours worked per week, as reported by working children, varies significantly between CLMRS projects, from 6 to 10 hours per week for projects in Côte d’Ivoire and from 2 to 4 hours for projects in Ghana. Similarly, the range between minimum and maximum reported number of hours worked is very different from one CLMRS project to another (figure 3).29

The number of hours worked per week, as reported by working children, varies significantly from 6 to 10 hours for projects in Côte d’Ivoire and from 2 to 4 hours for projects in Ghana.

Figure 3a: Median and ranges of reported hours worked in cocoa per week for children in child labour, aged 10–17 years, by CLMRS project.

Figure 3b: Median and ranges of reported hours worked in cocoa per week for children in child labour, aged 10–17 years, by CLMRS project.

Note: Hours worked in cocoa per week as reported by children identified in child labour or in hazardous child labour. Each vertical line represents one CLMRS project. Outliers have been removed. Data source: Compiled data from monitoring visits under 7 CLMRS projects in Côte d’Ivoire and 3 CLMRS projects in Ghana which collect information on hours worked by working children.

What we conclude and recommend

Previous ICI analyses of child labour data from various sources suggest that children’s reported estimates of hours worked vary widely depending on how questions are structured (e.g. whether children are asked how many hours they work on a working day and how many days they have worked during the past week or whether they are asked how many hours they have worked on each individual day over the past week).30 Also, ICI's experience with data collection has shown that outcomes depend largely on how much time and effort the data collection agent devotes to helping the child provide an estimate. Therefore, we suggest that the differences in child labour intensity measured under the different CLMRS projects are likely due to differences in data collection methods, rather than actual variation in hours worked.

CLMRS implementers should be aware of the methodological challenges involved in collecting this type of information. They should:

ensure that data collection tools, interview techniques and enumerator training follow best practice guidance on survey techniques with children (such as in https://childethics.com/ethical-guidance)

use short recall periods (maximum one week) for questions related to time spent on certain activities

plan in sufficient time in each monitoring interview to go through this module, recognising how difficult it can be for children to give accurate estimates of time

use a simplified module to estimate work intensity for children below 10 years of age

Different CLMRS projects measure very different numbers of hours worked per week by working children.

These differences are likely due to differences in data collection tools, interview techniques and enumerator training.

If information on hours worked by children is collected, appropriate data collection techniques must be applied to ensure that the data is of sufficient quality.

How does child labour identification vary at different times of the year?

- Child labour identification rates for each month of the year, averaged over all CLMRS projects in the compiled data base.

- Child labour identification rate: number of children identified in hazardous child labour divided by the number of children interviewed during monitoring visits in a given month.

- Comparability of results across CLMRS projects is compromised by variation in recall periods in the data collection tools used by the different CLMRS projects.

The method we use

We calculate for each month of the year the rate of hazardous child labour cases identified, using the compiled data set of monitoring interviews from CLMRS projects in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, from all years for which data is available.

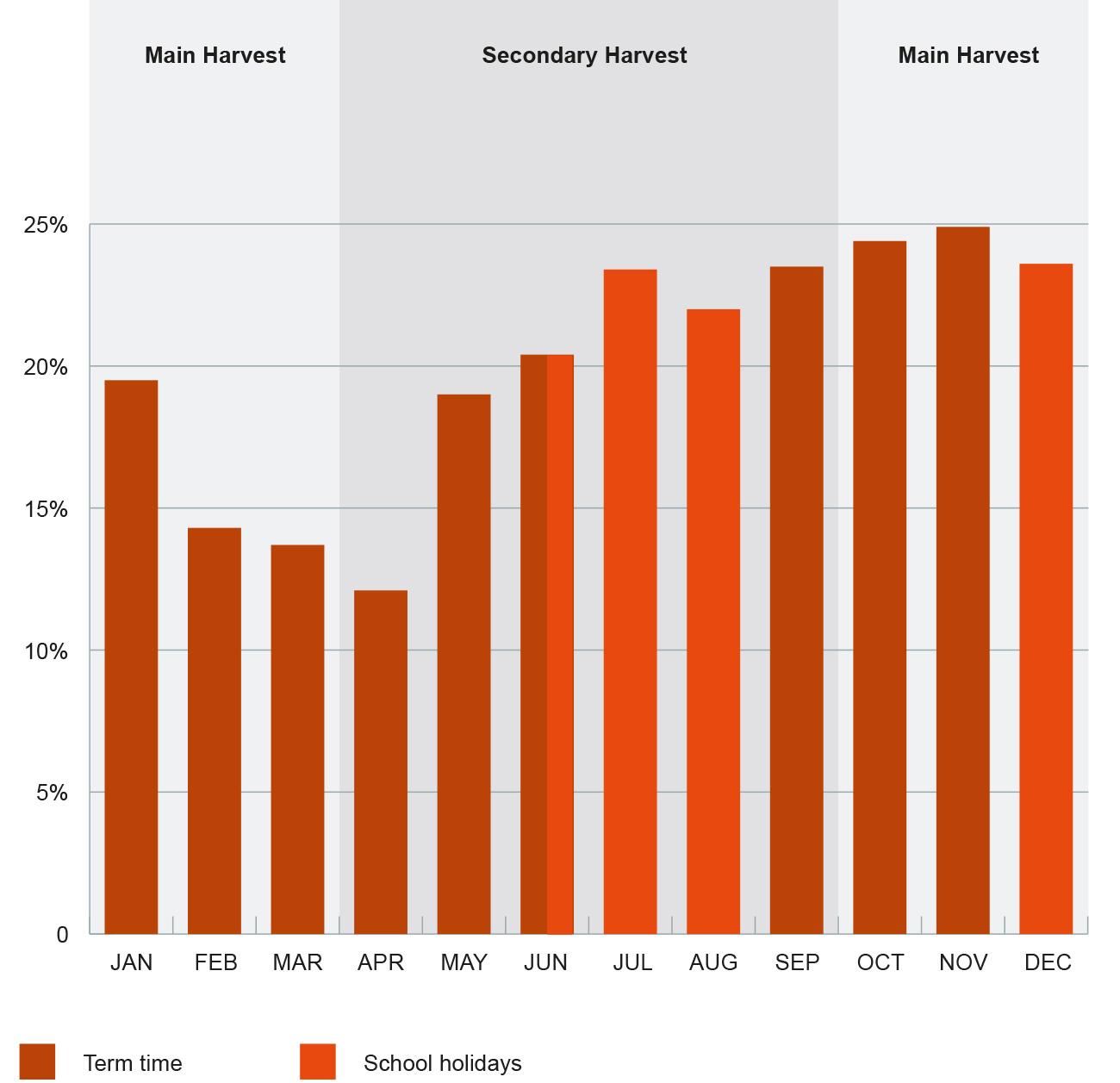

We then specifically examine two potential drivers of seasonal fluctuations in children’s engagement in farm work. These are fluctuations in labour demand in cocoa cultivation according to the agronomic calendar and in the availability of children enrolled in school according to the academic calendar. First, we compare child labour identification rates within and outside of the peak cocoa harvest season, which falls in the months between October and January in both Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. During this period, additional hands are needed on the farm for harvesting. Second, we examine how child labour identification differs depending on whether an interview is held during or outside of school holidays. First, we compare interviews held during the Christmas break, usually between 22 December and the first week of January (with slight variations from one year to the other and between the two countries31), and those held during the harvest season while school is still on. Second, for the period February to September (i.e. after the end of the main harvest season), we compare interviews held during and outside of the summer holidays, which roughly coincide with the month of August and the first half of September (again with slight variations from year to year and between the two countries32).

Our data reveals a pattern of seasonality for child labour identification, i.e. the likelihood that an interview will detect a case of child labour varies systematically over the course of the year. The seasonal pattern of child labour identification probably follows roughly the seasonal pattern of child labour incidence, but reporting may lag behind the actual incidence. In fact, some of the questionnaires used for child labour identification under different CLMRS specify reference periods for a child’s engagement in hazardous work of up to 12 months, which should in theory smooth out child labour identification rates over the course of the year. However, we see a strong seasonal fluctuation in child labour identification even if data collection tools use reference periods of 12 months, which suggests a reporting bias towards a short recall period. In other words, children are more likely to report on work they have done in the immediate past, rather than providing an accurate review of their engagement in work over a specified period of several months to a year.

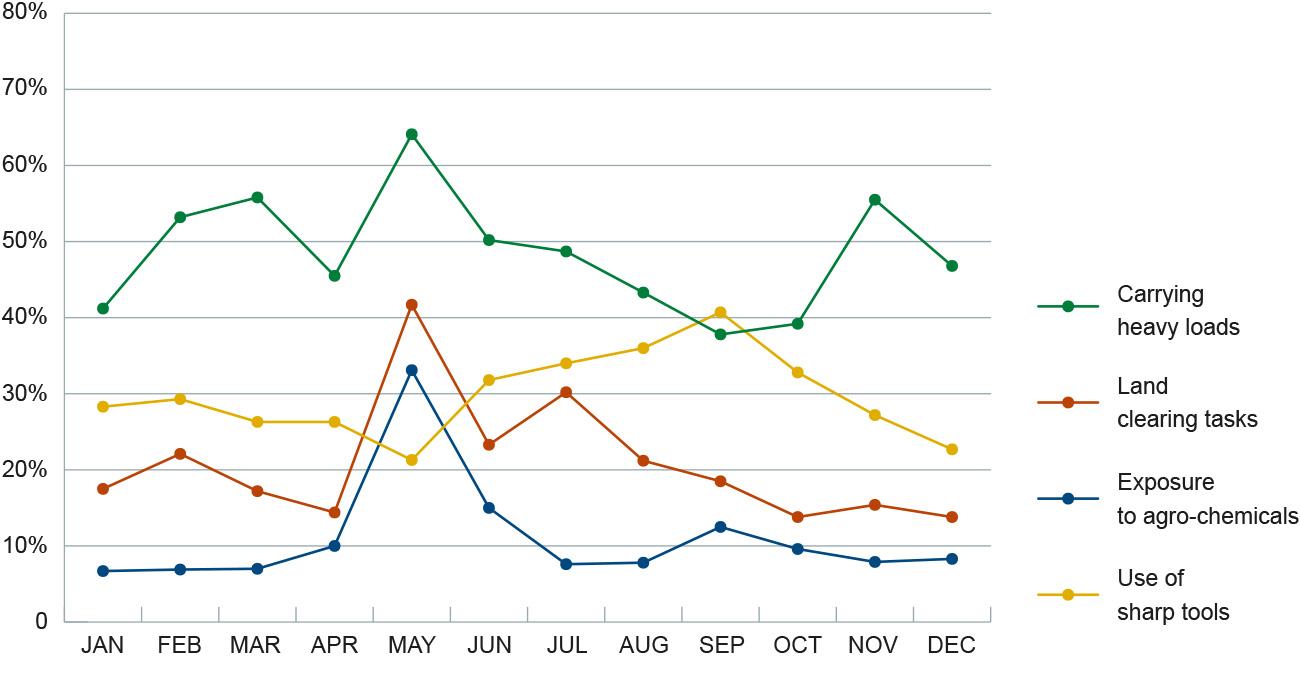

We also look separately at the seasonal fluctuation in reporting of specific types of hazardous tasks. Because the data collection tools applied under the different CLMRS use slightly different lists of tasks, all based on the national legislative frameworks but aggregated differently, we classify the hazardous tasks reported into four broad categories: carrying of heavy loads, land clearing, exposure to agro-chemicals and use of sharp tools (e.g. for the opening of cocoa pods or for the maintenance of plantations).

What we find

How does child labour identification, and reporting on specific hazardous tasks, fluctuate over the course of the year?

Within the compiled data set of child interviews, we find that child labour identification rates fluctuate strongly over the course of the year (figure 4). We can see that, on average, children are more likely to be identified in hazardous child labour when the interview takes place in the months between July and December. The likelihood of identifying a case of child labour is lowest if the interview takes place in February, March or April. Note that the rate is defined as the number of cases identified per number of children interviewed, and hence is independent of fluctuations in the numbers of interviews held per month.

Figure 4: Child labour identification rates, by month in which the interview was held.

Note: Child labour identification rates are defined as the number of children identified in child labour, in a given month of the year, divided by the number of children interviewed during monitoring visits in that month of the year. Data source: Compiled data from monitoring visits under 12 CLMRS projects in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

When monitoring visits take place during the peak harvest season (October to January) or during school holidays, the likelihood of identifying cases of child labour is higher.

When we divide up the year according to the cocoa harvest cycle, we find that hazardous child labour identification rates are on average higher by 5.4 percentage points when the interviews are held during the peak harvest season (October to January) than when they are held outside the peak harvest season (18.4% outside the main harvest period as against 23.9% within the main harvest period; the difference is statistically significant at the 1% level).

When we divide up the year according to the academic calendar, we find that within the harvest period, the likelihood that a child is identified in hazardous child labour is 8 percentage points higher when interviewed during the Christmas school holidays than during term time (31% for an interview held in the Christmas break as against 23% for an interview held between October and January but outside the Christmas break; the difference is statistically significant at the 1% level). We also find that the likelihood that a child is identified in hazardous child labour is 3.6 percentage points higher when interviewed during the summer holidays than when interviewed during term time outside the peak harvest period (21.3% for an interview held during summer holidays as against 17.7% for an interview held between February and September but outside the summer holidays; the difference is statistically significant at the 1% level).

How does children’s engagement in different types of hazardous tasks fluctuate over the course of the year?

The data also shows different seasonal patterns in the reporting of different types of hazardous tasks (figure 5): carrying heavy loads is recorded most frequently in February, March and May, and again in November and December; the use of sharp tools is recorded most frequently between June and October; exposure to agrochemicals is reported with a marked spike in May and June; and land clearing is reported most frequently between May and July. When we compare these patterns with the agronomic calendar for cocoa cultivation, we conclude that the reporting of specific hazardous activities follows the incidence, with a few weeks of time lag. For example, the peak season for application of agro-chemicals according to the agronomic calendar is March to April, but the reporting peak is in May.

Figure 5: Seasonality patterns for different hazardous tasks: carrying heavy loads, use of sharp tools, exposure to agro-chemicals, and land clearing.

Notes: Shares of children reporting that they have carried heavy loads, engaged in land clearing, been exposed to agro-chemicals or used sharp tools, among all children identified in hazardous child labour. Data source: Compiled data from monitoring visits under 12 CLMRS projects in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

What we conclude and recommend

As a general insight concerning the value of CLMRS data, CLMRS which collect data continuously over the course of the year can provide unique insights into seasonal patterns of child labour in cocoa production in West Africa. In that sense, they are highly complementary to child labour prevalence survey data, which is usually based on a one-off data collection exercise over a short time period.

The compiled CLMRS data shows that children are identified in child labour throughout the year. However, the likelihood that a monitoring visit identifies a case of child labour is higher during certain periods of the year, most notably:

- during the peak harvest season

- during school holidays

Hence, for a CLMRS to capture a high share of child labour cases, monitoring visits could be intensified during certain periods of the year: months in which labour-intensive farm work is conducted should be prioritised, as well as school holidays. Whether this is feasible depends of course on the CLMRS arrangements, notably the agents’ working arrangement: part-time agents who are themselves farmers may find it difficult to hold more interviews during the labour-intensive season, but if external agents are hired for data collection once per year, then it is likely that more cases of child labour will be identified if this data collection is scheduled during, or directly after, harvest and school holiday periods. In any case, these results point to the importance of informing monitoring agents and other staff involved in CLMRS management of typical seasonal patterns in child labour identification and of putting in place operational strategies to minimise the risk of overlooking cases of child labour in this period.

Different types of hazardous tasks done by children have different peak seasons over the course of the year. While carrying heavy loads and the use of sharp tools are tasks which are engaged in throughout the year, exposure to agro-chemicals and land clearing are more concentrated at specific times of the year. CLMRS implementers should use this information to tailor awareness-raising efforts, for example by scheduling focused awareness campaigns on specific hazards just before or during the peak periods for specific risks. This could help to ensure that participants perceive the awareness-raising sessions as directly relevant for their everyday work realities, and also to prevent awareness-raising fatigue, by altering topics over the course of the year.

- Children are identified in child labour in cocoa throughout the year, but there are periods of the year when child labour identification rates are higher.

- If monitoring visits take place during the peak harvest season (October to January), or during school holidays, the likelihood of identifying cases of child labour is higher.

- Different types of hazardous tasks follow different patterns of seasonality. The contents of awareness-raising sessions could be altered over the course of the year according to the peak seasons for specific hazards, in order to increase their relevant and prevent awareness-raising fatigue, and thereby make them more effective.

How effective are different types of monitoring visits for identifying child labour?

- Data from monitoring visits under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Child labour identification during home visits as compared to farm visits.

- Home visit / farm visit: Under most CLMRS, monitoring agents visit farmers in their homes to conduct interviews about children’s engagement in farm work. Under some CLMRS, these home visits are then complemented by random visits to cocoa farms to check on-site whether any children are working on the farm and what types of tasks they are doing.

Under ICI-implemented CLMRS, a farm visit is recorded only when a child is seen working. Therefore, it is not possible to calculate a “child labour identification rate” for farm visits which could compared to that from home visits.

Child information collected at farm visits focuses on tasks done and does not allow an assessment of the child’s situation more broadly.

Farm visits data are available only from ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, hence the validity of results for other contexts is unclear.

The method we use

We compare the outcomes of monitoring visits to farmers’ homes with those of monitoring visits to the farmers’ cocoa farm. We use data from ICI implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire from which we have records of home and farm visits to substantial numbers of farmers. This data allows us to directly compare outcomes of interviews with the same child depending on where the interview took place.33

According to the standard ICI CLMRS protocol, after monitoring agents have visited a cocoa producer at home to register all basic household information and talk to all children aged 5–17 years about their engagement in hazardous child labour, they also visit producers’ farms. If monitors see children working on the farm, they survey them on the types of tasks they are doing. However, an entry into the data base for a farm visit is made only if a child is found working.34 It is therefore not possible to directly compare child labour identification rates from farm visits to those calculated for home visits. To draw conclusions on how effective these two types of monitoring visits are in comparison, we examine the counts of child labour cases identified and compare the profiles of children identified in child labour through home as against farm visits.

What we find

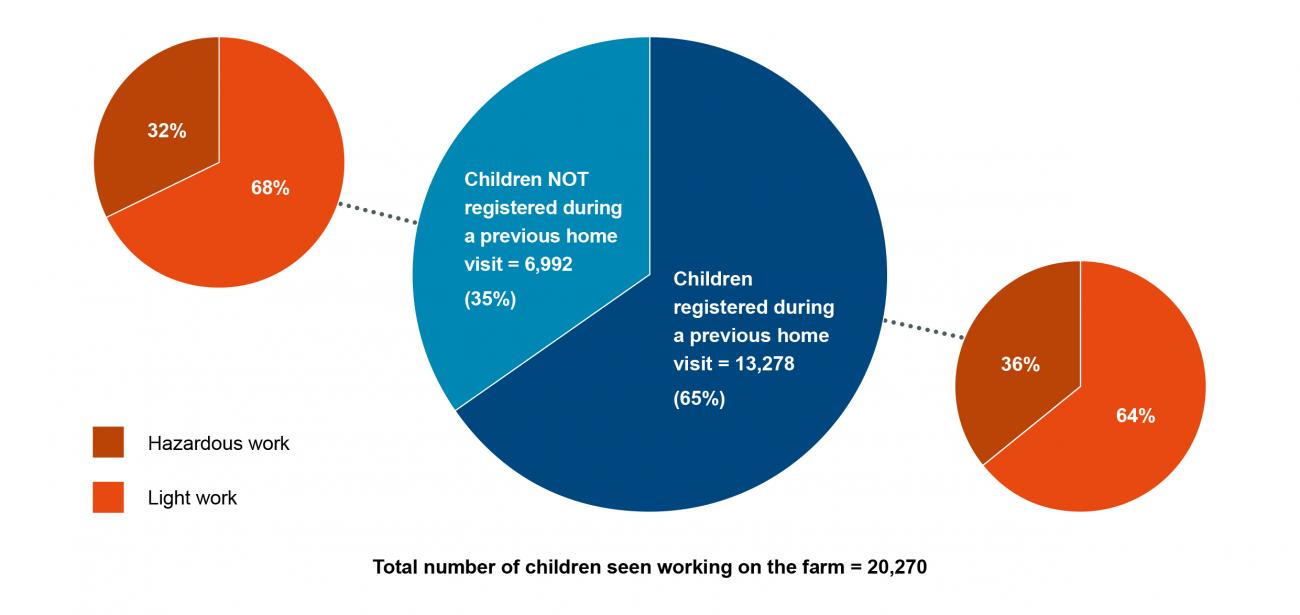

Many more children are identified in child labour during home visits than during farm visits. In the first place, this reflects the fact that for home visits monitoring agents have the explicit objective of meeting and talking to all family members, whereas the farm visit is a complementary random check.

Of the children who reported not doing hazardous child labour when visited at home, only 2% were subsequently found to be doing hazardous work on a farm visit (but given that not all children are covered with farm visits, as they are intended as spot checks, and that not all farm visits are recorded, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions from this).

Figure 6 breaks down the sample of all children covered by the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire (i.e. all children ever recorded at any monitoring visit) according to whether and on what occasion they were identified in hazardous child labour.

Among children who were seen working when the agent visited the farm, approximately 36% of these engaged in hazardous work. The remaining 64% of these children were doing light work only.

Figure 6: Child labour identification at home and farm visits amongst all children covered by ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

*35 Including both children who have been registered during a previous home visit and children not registered before, even if the farmer’s home has been visited.

However, next to verifying the information collected during home visits, farm visits serve another important purpose: the data shows that, in fact, farm visits help to identify working children not captured at all during home visits. Considerable numbers of children seen by agents helping on the farm had not been registered at all during a previous home visits (see figure 7). The total number of children identified for a first time at a farm visit is 6,992, which is approximately 1 in 3 children seen working on a farm. Amongst these, the share doing hazardous tasks is 32%, which is a very similar rate as in the case of those children who were recorded during a previous home visit.

The total number of children identified for a first time at a farm visit is 6,992, which is approximately 1 in 3 children seen working on a farm.

What we conclude and recommend

The data shows that home and farm visits are highly complementary means of monitoring child labour use by cocoa farmers and that neither type of visit could replace the other.

Importantly, farm visits can provide an additional monitoring layer to ensure that any child labour use by cocoa producers covered by the CLMRS is identified and can be addressed. They allow us to capture children living in the household who are absent at the time of the home visit and not mentioned by parents, as well as children not living in the farmer’s household (for instance, children working on their relatives’ or neighbours’ farm). Unfortunately, the data collection tools applied during farm visits under ICI CLMRS are limited to information about work done by children and do not include any additional information about these children, except their names and identifier codes (the data collection tools are designed on the presumption that any demographic characteristics, schooling, vulnerability indicators, etc, of the child are collected at home visits). Hence, the available data does not allow us to better understand the circumstances and profiles of these cases of working children.

Two important recommendations emerge from these findings:

First, CLMRS should include mechanisms to capture working children who remain invisible on farming household rosters recorded by the monitoring agents. One option is for agents to visit cocoa farms on a spot check basis. Another option may be to include in the farmer interview more detailed questions on extended family members or non-family farm workers, and then follow up on any information provided, for example, by visiting workers mentioned by the farmer and surveying them about involvement of children in the paid farm work or by requesting to speak directly to children in the extended family who come to help out.

Second, when farm visits take place, data collection tools should be aligned with those used during household visits and collect information on demographic characteristics and situation of any children seen working. This data should then be used to understand the profiles of child labourers not registered during home visits and to develop strategies to capture these cases more systematically and address them adequately.

Visits to homes and on farms are highly complementary tools to monitor child labour use by cocoa farmers.

Farm visits are one option for capturing child labour cases which remain invisible when screening only direct members of the farming household (e.g. children working on their relatives’ or neighbours’ farm), but other less costly options could be tested.

Currently available data provides insufficient understanding of the profiles of children not registered during home visits but seen working on the farm. CLMRS should collect more detailed information on these children to allow their situation to be adequately addressed.

Which monitoring agents are more effective at identifying cases of child labour?

- Data from monitoring visits under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Locally based monitoring agents: under ICI-implemented CLMRS, child labour monitoring visits are conducted by locally based agents, often themselves cocoa farmers trained by ICI on child labour, survey techniques and child safeguarding, who are usually hired on a part-time basis and remunerated through a lump-sum payment if they complete a minimum number of monitoring visits per month.

- Detailed agent characteristics are currently available only for a subset of child interviews held under ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, which works through locally based monitoring agents. The validity of results for other contexts unclear.

The method we use

We examine how the likelihood of identifying cases of child labour through monitoring visits changes with the profile of the agent conducting the visits. We use data from the ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire, where all agents are members of local cocoa producing communities who have received special training in child labour, survey techniques and child safeguarding, and who collect data from all members of farming households using mobile data collection applications. These agents are hired on a part- time basis and receive a lump-sum payment if they complete a minimum number of monitoring visits per month. All of the results reported below therefore apply to the specific context of locally based agents who conduct child labour monitoring visits under CLMRS, similar to the ICI model.

We have the following information about monitoring agents available for analysis: gender, level of education, place of residence, the number of months the agent has been in service within the CLMRS and the number of farming households covered by the agent. The place of residence allows us to differentiate monitoring visits by whether the monitoring agent who holds an interview is living in the same community as the cocoa farmer interviewed or in a different community.

Descriptive statistics for these agent characteristics and how they are correlated with each other in our data set are presented and discussed in an online appendix.

To understand how agent characteristics potentially affect the outcomes of the interviews, we use multivariate analysis which allows us to separate the effects of agent characteristics from the effects of the profile of communities, households and children covered by each agent. We use a sample of approximately 7,250 child interviews for which we have information on all the agent characteristics mentioned above,36 to run a series of logit regression models specified as follows:

the dependent variable is whether a child has been identified in hazardous child labour37

as explanatory variables we sequentially add the different agent characteristics

- as control variables, we include a set of child, household and community variables which we know to be correlated with child labour – specifically, we control for the child’s age and sex, the number of household members, whether the household head and spouse can read and write, whether the household is headed by a woman, whether the community has a primary school and electricity grid access, and whether it is accessible by road all year round

We sequentially add the agent characteristics to the regressions in order to spot potential instances of multicollinearity

Agents are members of local cocoa producing communities who have received special training. They are hired on a part-time basis and receive a lump-sum payment if they complete a minimum number of monitoring visits per month.

What we find

The results from the regressions (table 3) suggest that, after separating out other factors:

Monitoring agents with at least secondary education are more likely to identify child labour cases: on average their child labour identification rates are 13 percentage points higher than those of agents with lower levels of education.

Female agents are more likely to identify child labour cases: on average their child labour identification rates are 19 percentage points higher than those of their male colleagues.

Agents living within the same community are less likely to identify cases of child labour, by around 4 percentage points.

Monitoring agents with more experience are more likely to identify child labour cases: with an additional 10 months of experience an agent has, the likelihood that their interview identifies a case of child labour increases by 2 percentage points on average.38

Agents covering smaller numbers of farmers are more likely to identify child labour cases: when the number of farmers covered by an agent increases by 10, the likelihood that an interview identifies a case of child labour decreases by 2.5 percentage points.

Table 3: Relationship between monitoring agent characteristics and child labour identification.

Marginal effects from logit regression, where the dependent variable is: whether interview resulted in identification of a case of child labour.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent has secondary education or higher | 0.1304*** | 0.1240*** (0.0155) | 0.1093*** | 0.1109*** | 0.1272*** |

| Agent is female | 0.2418*** (0.0301) | 0.2169*** | 0.2304*** | 0.1861*** | |

| Agent lives within farmer's community | -0.0447*** | -0.0441*** | -0.0393*** | ||

| Agent's experience (in months) | 0.0016*** | 0.0023*** | |||

| Number of producers covered by agent | -0.0025*** |

Notes: Additional control variables included in all regressions for which coefficients are not reported: child’s age and sex, number of household members, whether household head and spouse can read and write, whether household is headed by a woman, whether community has a primary school and electricity grid access and whether community is accessible by road all year. Marginal effects show by how much the rate of child labour identification changes with an incremental change in each of the agent characteristics. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1; standard errors in parenthesis.

Data source: ICI-implemented CLMRS in Côte d'Ivoire.

Figure 8: Agent characteristics affecting the likelihood of identifying cases of child labour.

What we conclude and recommend

In any CLMRS set-up, the agents in charge of data collection play a crucial role in achieving some of the system’s most important outcomes. In the ICI CLMRS model, monitoring agents constitute the primary point of contact between the CLMRS and the farmer. They explain the objectives of the system and conduct basic awareness-raising with all farmers. Even if agents receive very similar training packages on child labour, interview techniques, CLMRS questionnaires and child safeguarding, each agent brings to this job their personal skills, talent, experience, social capital within the community and a level of commitment, which will have a strong impact on the outcomes of their monitoring work.

The regression results suggest some systematic patterns with regard to what profiles of locally based monitoring agents are particularly effective at identifying cases of child labour through household visits. The most salient conclusions from the available data are that female agents are more effective than their male colleagues and that agents with higher education levels are more effective than those with primary education only. There is also some evidence that with experience, agents become better at identifying cases of child labour (although the effect of accumulating experience is relatively weak, potentially because it is counterbalanced by other effects such as decreasing motivation for the job or fading of the effect of initial training). The likelihood of identifying cases of child labour also decreases slightly on average as agents cover more farmers, which may be because they have less time available for each visit.

The analysis shows that female agents are more effective at identifying child labour cases than their male colleagues, and that agents with higher levels of education are more effective than those who have only been to primary school.

In the context of the standard ICI CLMRS model, where community members trained as monitoring agents interview farming families within their own or neighbouring communities about child labour use, the data shows that agents are slightly more likely to identify cases of child labour outside of their own communities (even though the difference is rather small). One possible interpretation is that if the agent knows a farmer well because they live in the same community, this poses a slight disadvantage to the chance that the interview will detect cases of child labour. However, it is important to note that if we compare child labour identification rates across CLMRS models working with different types of monitoring agents (community members, cooperative staff, hired enumerators), there is no clear pattern to show that community outsiders are more effective at child labour identification than community members. This is because the effect of agent types is overlayered with other differences across the CLMRS models from which we have data. To conclude, there is indicative evidence that community outsiders may be slightly better positioned to detect cases of child labour than community members, but the available data does not allow us to draw clear conclusions on this question. Additional qualitative research should be undertaken in order to better understand the dynamics involved in agents monitoring child labour use in their own communities and to optimise CLMRS arrangements accordingly.

In the implementation of its ALP programme (for more details see Box 1), PMI recognised that women

can take on important roles as positive agents of change, but they can also be a vulnerable group in many

rural environments.

As a core element of the ALP programme, field technicians in countries where PMI sources tobacco verify farmers’ compliance to the ALP Code by conducting farm-by-farm monitoring. They engage with farmers and workers to ensure that practices that are not aligned with the Code are identified and addressed. Agronomy as a profession has been traditionally and predominantly performed by men. In spite of this, and even though women are in many contexts facing various challenges as field technicians, PMI increasingly supports the involvement of women both on the field and in supervisory roles. PMI values the additional gender sensitive insights and expertise that women can bring to a team, particularly in engaging openly with female farmers, workers and family members.

As an example, PMI’s local affiliate in Pakistan found that male field technicians were unable, due to cultural paradigms, to directly engage with women on the farms. This is why, in 2019, they deployed a team of 10 women (“ALP Monitors”) to raise awareness about ALP standards. The team engaged with over 250 women across 250 farms mostly through house visits and recorded significant improvements, especially in safe working practices. However, despite the positive experience in some markets, it remains a challenge to attract women for the role of field technicians.

PMI also recognises that women are agents of change in the fight against rural poverty and child labour. Women are known for being more open to learning and changing, especially when it comes to issues related to their children’s well-being and safety in general. When they are engaged in awareness-raising programmes, they pass on learnings to their families and influence them toward a safer and more inclusive work environment without child labour. Based on these learnings, PMI included women’s empowerment as one of the guiding principles on ALP Step Change and rolled out targeted initiatives for women farmers and workers such as trainings, village savings and loan associations and supporting the establishment of small-scale businesses.

For more information, please see Agricultural Labor Practices Progress Update – Empowering Women for Change (PMI – Philip Morris International).

However, the results allow for the following recommendations for CLMRS project managers, in terms of agent recruitment and work arrangements with agents:

A secondary education level should feature amongst the key selection criteria when monitoring agents are recruited. If qualified candidates with secondary education are difficult to mobilise, additional training to strengthen relevant skills, or additional supervision and support, might be provided for agents with lower education levels.

Efforts should be made to recruit and retain more female monitoring agents, which has proven

to be challenging in practice. ICI is planning to explore in a follow-up study which recruitment channels, work arrangements and support measures can be employed to help reach this objective.Community-based agents should be helped to reach farming households outside of their own community (e.g. by ensuring they have bicycles or motorcycles at their disposal or by paying transport allowances).

The number of farmers covered by an agent should be set in accordance with the time the agent can dedicate to the job, to ensure that agents have a realistic time budget available to conduct each monitoring visit with due care.

- Agents should be incentivised to stay in the job after they have acquired experience.

There are of course many agent characteristics which may be at least as important as the ones examined here, but which are difficult to measure and not captured in our data (such as, the agent’s ability to gain children’s trust, his or her social standing and reputation within the community and his or her relationships built with individual farmers). Also, the insights here apply only to the context of a CLMRS model which uses community-based agents for child labour monitoring and are based on data from Côte d’Ivoire only.

Box 2 presents experience by PMI’s under their Agricultural Labour Practices (ALP) programme, where the effectiveness of the programme could be enhanced by training women as field technicians and recognising women’s role as change agents within the family and the community.

- The likelihood that a community-based agent identifies a case of child labour through a monitoring visit varies with their demographic profile and work experience.

- Community-based agents with at least secondary education, as well as female agents, are more effective at identifying cases of child labour.

- Agents are also more effective when they are more experienced in doing monitoring interviews and when they cover fewer farming households.

- Agents are slightly more effective in identifying cases of child labour when they visit farming households outside their own community, an observation to be followed up with more qualitative research to understand why this is the case.

- These results are applicable only to the context of CLMRS models working with locally based agents. The available data does not allow us to compare across CLMRS models with different types of agents hired for monitoring, such as cooperative staff or external enumerators visiting the community only for data collection.

References

24 Tulane University (2015) Survey Research on Child Labor in West African Cocoa Growing Areas. Final Report. Assessing Progress in Reducing Child Labor in Cocoa Production in Cocoa Growing Areas of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

27 ICI (2021), Risk Models to Predict (Hazardous) Child Labour.

28 See for example, the ICI report The Impact of ICI’s Community Development Programme in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire on Child Labour (2020).

29 Note that the median and ranges are independent of child labour identification rates, given that they are based on children identified in child labour only.

30 Results available upon request from ICI.

31 We consider the exact official start and end dates of the holidays for each year according to the ministries of education.

32 We consider the exact official start and end dates of the holidays for each year according to the ministries of education.

33 Monitoring visits can of course also take place in other settings, such as in schools, at community meetings, at the margins of training and awareness-raising sessions, etc. We compare here home against farm visits, because for these interview types we have sufficient data available.

34 ICI has recently revised its data collection forms so that in the future, records will also be available for farm visits where no children were found working.

35 Including both children who have been registered during a previous home visit and children not registered before, even if the farmer’s home has been visited.

36 The 7,250 interviews included in this analysis constitute approximately 7% of the available child interviews held under ICI implemented CLMRS in Côte d’Ivoire.

37 We use a binary indicator of whether an interview with a child resulted in the identification of a case of hazardous child labour.

38 From anecdotal evidence, we know that some agents who have been in this role for a very long time lose motivation, which may also imply a decrease in their child labour identification rate. However, our data does not allow us to establish such a dynamic in quantitative terms, because the number of interviews conducted by agents with long experience is relatively small (less than 3% of the interviews were conducted by agents with more than 3 years of experience).